It takes a stroll via the three-color-coded Hungarian Pavilion for visitors to realize the vision through an interwoven “Manifesto” that highlights successful examples of architects who have excelled outside their scope of specialization, while brilliantly interlacing all factors of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025’s theme: Intelligence. Natural. Artificial. Collective. We talked about this and much more with the curator Márton Pintér.

Márton Pintér, born in 1991 in Kecskemét (Hungary) and curator of the Hungarian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025, adopts the pavilion concept by exploring how economic logic is increasingly prevalent in architecture, where profit is prioritized over creativity. Pintér guided us through his unique vision dynamically and amusingly, showcasing architects who have unlocked their creativity in various professional fields after graduating from architecture school. An idea that had been churning for a decade.

You have shared with me that curating the Hungarian Pavilion was your first time curating. Would you like to tell us how it all came to be, and, from your viewpoint, how your experience helped shape your role as a curator?

I’ve been preparing for this specific event (I mean the Biennale) both unintentionally and intentionally in the past decade. So honestly, it is a rather personal topic… My first professional experience was an internship at OMA*AMO, where I happened to be working on Monditalia, one of the leading exhibitions of the Venice Biennale in 2014, curated by Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli. It was a very demanding project, requiring me to apply the alternative use of the architectural knowledge I acquired at the university. It was my first time experiencing that research has priority over the entrance situation. After I returned home and graduated, I attempted to apply the experience I had gained abroad, but it quickly became clear that it wasn’t going to work. So, I figured “okay then”, I will practice architecture just to experience every aspect of it on my skin – I sort of sacrificed my architectural career for the sake of “questioning its relevance” and so it became my ars poetica. Ten years had passed, and I thought it was time to conclude everything into a thesis, which later became my competition entry for this year’s Biennale. Another year, and on the opening, it almost felt like I had not only organized a funeral of “my architect self” but also attended to it, haha! However, I’m glad this major personal aspect remained invisible, and it doesn’t make sense in the exhibition. And yes, this was my first time curating.

Could you describe the curatorial narrative that you aimed to construct through the selection of architects and their works, and how this narrative evolved during the process?

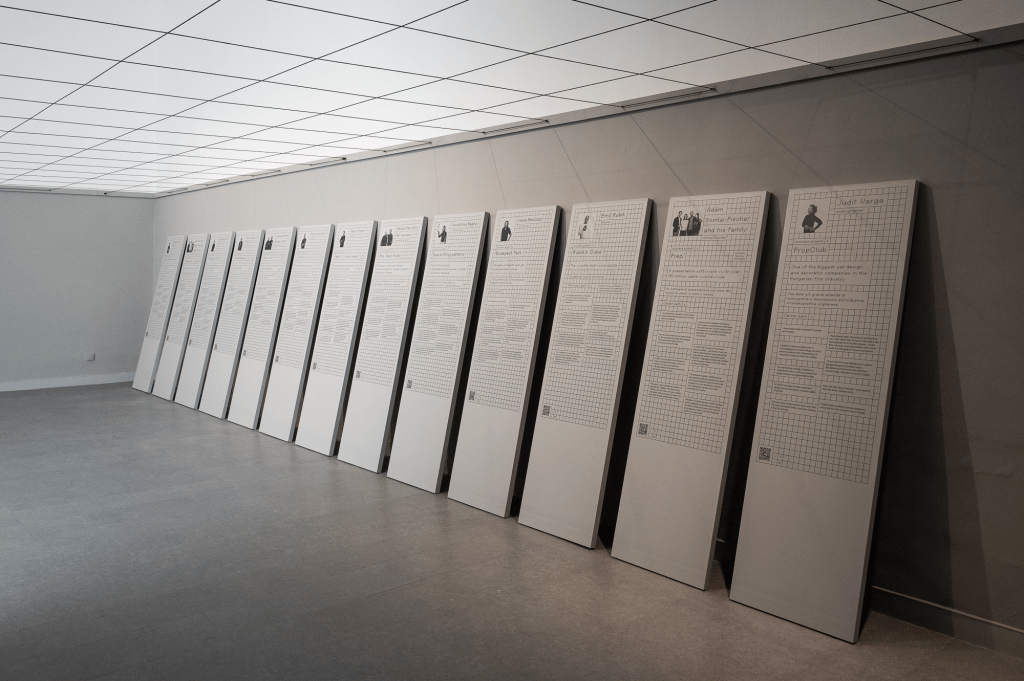

The narrative is straightforward: architecture is not equal to the construction industry. Through my research for my doctoral thesis, I found that architects credit many “drop-out” or “career-finder” stories. I created a basic filter before I decided to start collecting the stories: their projects are internationally known, they studied or practiced architecture, there is no overlap between the “export disciplines”, and they live in Hungary. So, it all started with the projects. I reached out to the organizers, invited them to join, and they agreed. Then, my small curatorial team (comprising two of my former students, András and Ingrid) had to keep this large group of high-level individuals, who were exhibitors, united behind a harsh narrative that aligned with the title’s premise. It was an outstanding cooperation between the curatorial team and the exhibitors, and it is still unbelievable that we managed to do it without any compromises. It is amazing.

CURATORSHIP ACCORDING TO MÁRTON PINTÉR

Did the architecture drive the story, or did your conceptual framework shape the types of practices you sought out? Regarding the display of Successfully Exported Architectural Knowledge and Success Stories to Inspire, the two sections showcasing architects’ work on their success projects outside the profession, as a curator, how did you decide to allocate specific display devices ‒ spatial layouts, materials, or multimedia ‒ you employed to mediate architectural ideas, and why?

It is both architecture and conceptual framework-driven. It all starts from one point and leads to many. Every story shares architecture as its common origin, yet each exhibitor represents a distinct discipline, offering a broad spectrum of perspectives as a vanishing point.

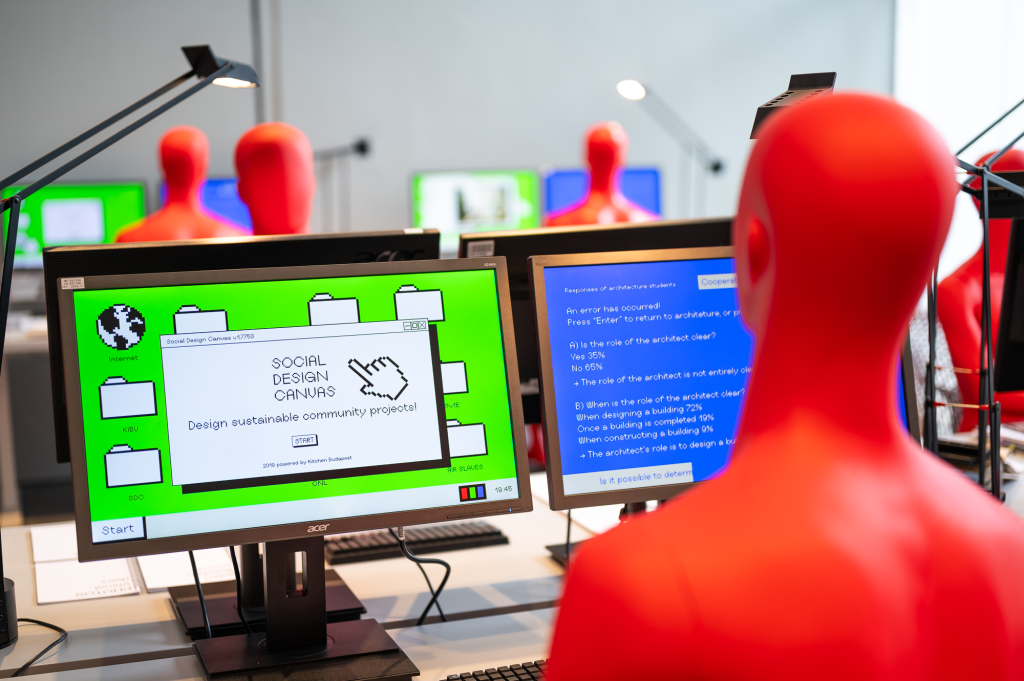

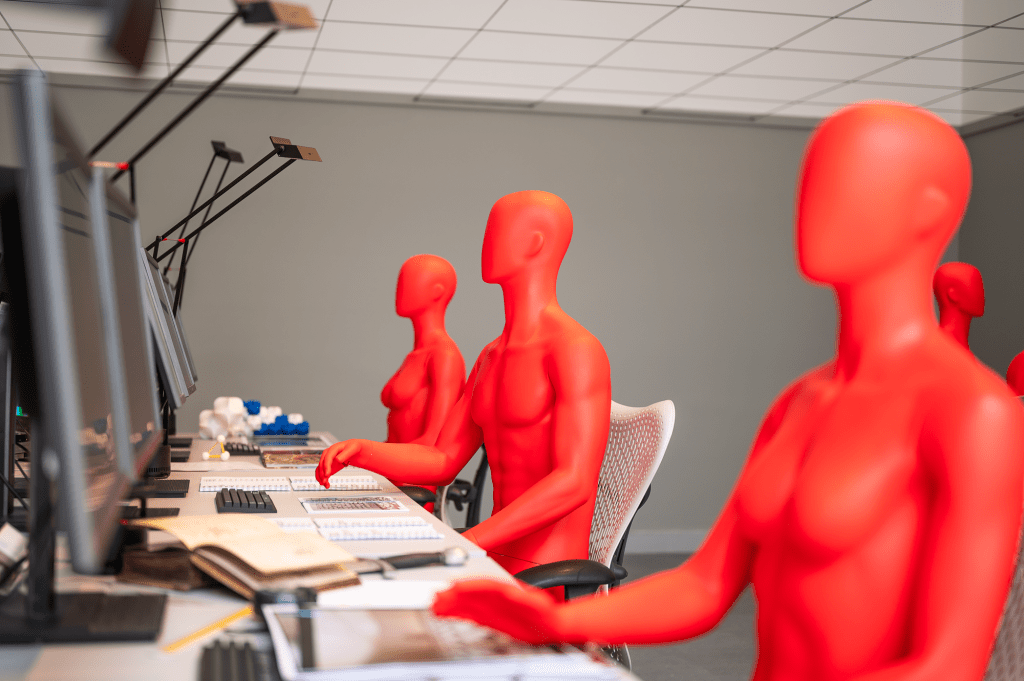

My intention was to create content that is both rich and easy to digest. So, I went for the stereotypical corporate standards for the set and the depressing office activity for the setting. About the arrangement – it went smoothly, there was an immediate common agreement among the exhibitors and the curatorial team on which project goes where: the Somlai-Fischer family takes the “negotiation room”, the copyright kings (Mr. Losonczi and Mr. Rubik) simulating a discussion in the lobby space, the much-respected generational Kaláka music band takes the oval without hesitation and all the other superstars are just enjoying their 9 to 5 at their work stations. What’s more important, though, is that an invisible ingredient to the spatial distribution is the layering. A strong title and scenography can convey the concept in seconds, but you could also spend minutes on just one story.

The Hungarian Pavilion landed a fresh take on how architectural knowledge is inherently natural, artificial, and collective all at once, so it can often be put to much better use outside the framework of the construction industry. Were there any challenges executing this concept within the pavilion’s allocated space?

Conceptually speaking, it was an unbelievable coincidence. Can you image what I felt after working on my concept for months already and then in December, 2023 Carlo Ratti is being introduced with his statement of “To face a burning world, architecture must harness all the intelligence around us”. I was all-in. Contextually, however, a statement (like our approach) allows us to ignore the existing exhibition space. The contrast between a classic pavilion and the radical content eventually made the exhibition even better. Talking about challenges… The suspended ceiling imitation is not only a strong set element, but also an essential aspect of the budget cut, as it literally halved the space and therefore lightened our razor-thin budget. The curatorial team also personally helped by waiving our commission fees. Another all-in, but this time quite literally, haha!

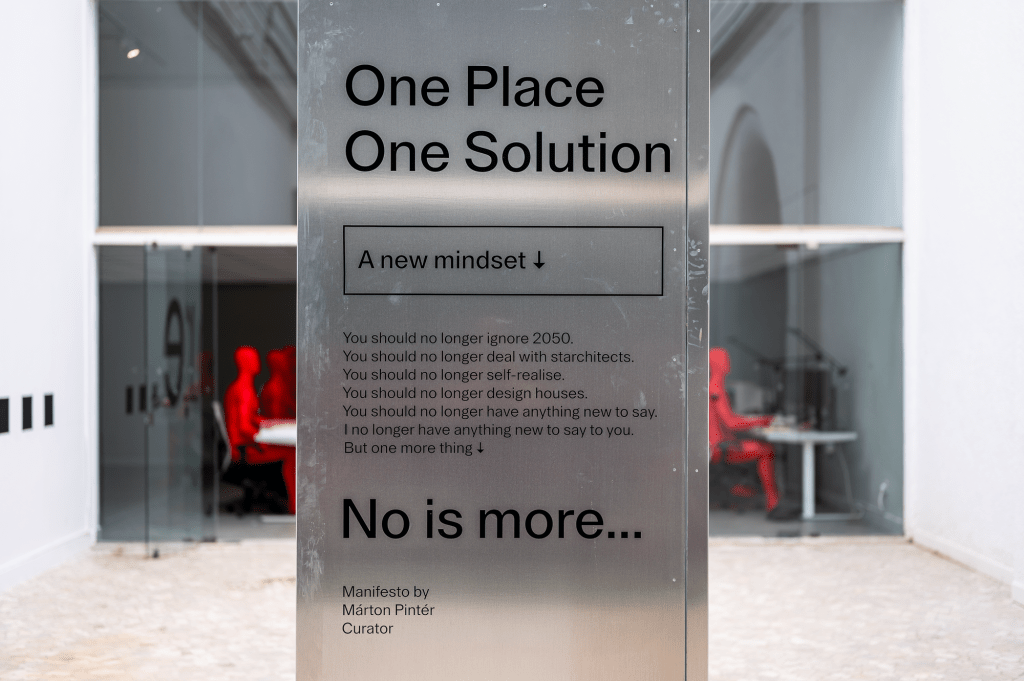

There Is Nothing to See Here is a strong statement or perhaps a manifesto. Say no to more, which is the official Instagram page for the Hungarian Pavilion. How did you develop these strong and impactful messages, and do you think viewers experienced this motif throughout the exhibition?

Thank you for emphasizing these two. The title is indeed a statement, while “No is more” is my take, which we can call a manifesto. The title has a lot of meaning to it, which I specifically made clear in my opening speech, so let me quote that:

- There is Nothing to See Here is a self-reflection.

- There is Nothing to See Here is a critique outward.

- There is Nothing to See Here is a police slang.

- There is Nothing to See Here is an invitation for discourse.

- There is Nothing to See Here is the title of the exhibition as well.

“No is more” was figured months after working on this project under that title. I knew I had to take a step back and simplify everything I wanted to deliver. Of course, it roots back to the most famous architecture meme “Less is more”, but what’s more important that it stands among all the “… is more” memes in the sense, that they all reflected to their age pretty well: Mies about modernism, Venturi about postmodernism, Rem about capitalism, Bjarke about individualism. And now it’s an unknown guy from a late-capitalist era just trying to raise awareness of saying yes to no when it comes to constructing Excel sheets out of concrete under unsustainably over-quantified working conditions. Placing a bet against the construction industry as an architect may be irresponsible; nevertheless, I hope I have effectively conveyed the idea behind “No is more…”.

THE HUNGARIAN PAVILION CURATED BY MÁRTON PINTÉR

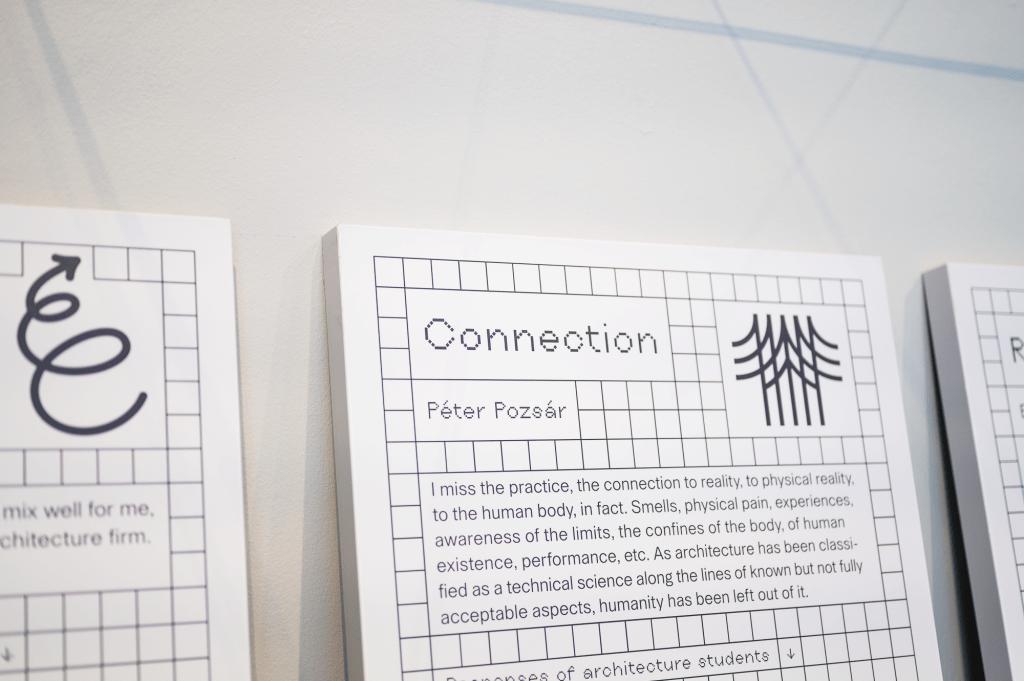

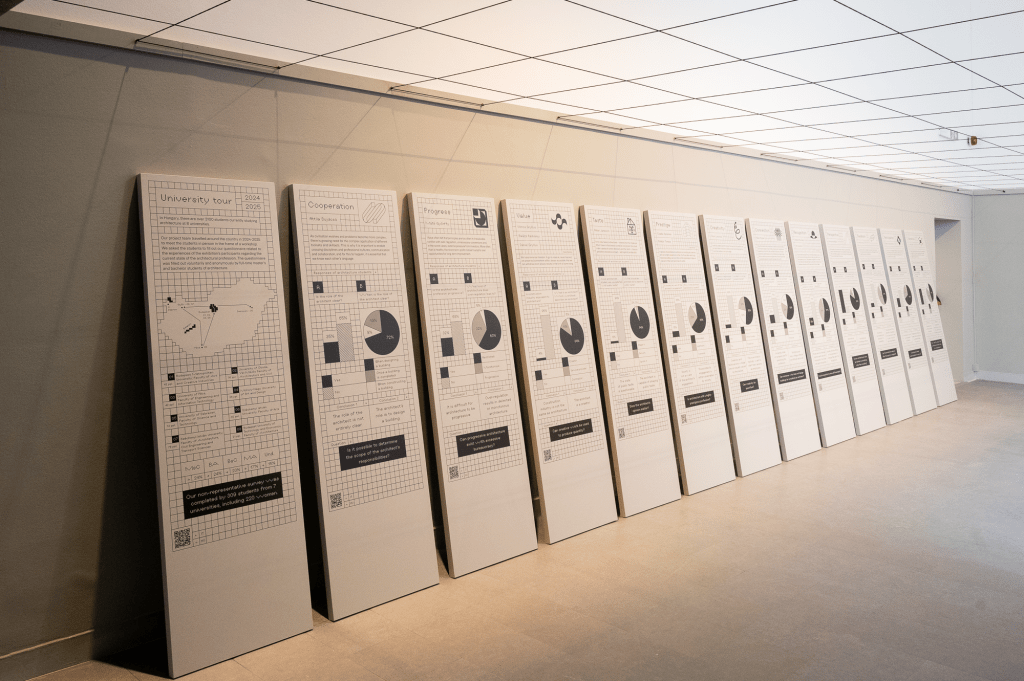

The exhibition’s content is divided into three categories, represented by an RGB color scheme. Red represents the participants, green signifies their successful projects, and blue marks the student reports on the state of architecture collected throughout a survey across Hungarian architecture universities. What is the impact of the blue section?

Based on my on-site experiences, I’ve found that students from all around the world – including those from larger, more renowned universities – are often grateful to confront some cold, hard facts that are typically taboo. If our student feedback is to have an impact, it must be organic, underground, and long-term. If so, I’m already happy to contribute to that indirectly. I recall that my former boss, Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, curator of Monditalia, had a large red sticker at his workstation that read “RIOT”, so I thought I’d leave this here. (Also, he wrote a prologue for our catalog titled Against Specialization; if you get that in your hands, I highly recommend reading it).

A survey of this quality and quantity has never been conducted in Hungary, either by a state commission, market research, or in an underground student-organized manner. We were the first to do it for good. If this blue section is not reviewed or discussed at home, I’d consider it an irresponsible and major fault on the part of those who make decisions. And I’m saying it as an Associate Professor myself, not as the curator.

What distinguishes the Hungarian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2025 from other pavilions?

There is Nothing to Distinguish Here.

In a global forum like the Biennale, how do you balance the representation of national identity with transnational or universal architectural concerns? Or was the idea of “Hungarianness” central to your curatorial vision, or deliberately recontextualized?

This question is the toughest. “Hungarianness” has unfortunately become no more than a cheap political catchphrase in the past decade or so. For a global forum like the Biennale, it is the most pretentious thing to come up with the idea of a self-celebratory national salon. So, it had to be deliberately recontextualized, which was the most challenging task in the whole process. All this was possible by creating parallel universes. One is for myself to keep my decade-old vision alive; one is for the amazing (still no words can describe what they’ve done) team to keep their ambition on the highest level, and one for the powerful ones to keep them busy with the politically acceptable “success narrative”. I mean, the title is There is Nothing to See Here after all, and with all the meaning behind I’ve just previously described, right? Busted.

What would Márton Pintér have in store for us in the future / next accomplishment?

My next accomplishment would be to secure a creative director or curator assistant position abroad somewhere. Anyone?

Lina Alshihabi