In a Venice increasingly dominated by speed, money, greed and much more, where only a certain art system dictates the pace, Osservatorio Sant’Anna offers a breath of fresh air. In the homonymous complex in the Castello district, at the end of via Garibaldi and a few steps from the Giardini della Biennale, a research group is giving hope to a building and an entire community. We interviewed Matteo Binci, curator and co-founder of the project.

Osservatorio Sant’Anna is many things: it is a tool, a device, a place, a space and, above all, a voice. A voice that opposes the economic dynamics that regulate purchases and speculation in the city of Venice. A voice for those who feel they do not have one. Created within the framework of the 2025 Architecture Biennale Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective., the initiatives of OSA (Osservatorio Sant’Anna) have welcomed and culturally enriched the Castello district, offering a place and shared moments for the community. Saving, in a sense, a building from becoming yet another hotel, a fake artists’ residence or a space for tasteless exhibitions.

We interviewed Matteo Binci, curator and co-founder of the project, sitting at a table a few steps from the Sant’Anna complex, in a very characteristic bar in via Garibaldi, under the light of a Cynar neon sign in the shape of an artichoke. In the ultimate expression of Venetian culture, on 15 November 2025, we listened to Matteo’s story, hoping that there might be a future for such a utopically necessary hope.

THE INTERVIEW WITH MATTEO BINCI

When and how was Osservatorio Sant’Anna founded, and who is involved?

OSA was founded by Matteo Binci and Maria Eugenia Frizzele, in collaboration with Lorenzo Perri and Sabrina Morreale from the Lemonot studio. It was established in 2025 but had been in development for the previous six months, in the second half of 2024. It was born from an intuition of Maria Eugenia Frizzele, a resident of Venice who lives in front of the church. We had met in previous years, had conversations and realised that we shared similar intentions and perspectives, so she involved me in this idea: to think about what the purpose and the reuse of the church of Sant’Anna could be. We had already begun working on a long-term proposal during the summer of 2024, and then Carlo Ratti, artistic director of the 2025 Architecture Biennale, issued an open call (Call for ideas) inviting studios from around the world, as well as informal citizen groups, to submit proposals. We had already begun to structure the entire project and used this opportunity to formally establish ourselves. We understood that the church needed an architectural firm (Lemonot, in fact), partly because the open call required the participation of an architectural firm with members under 35 years of age. We applied and were evaluated positively with a very high score. This was somewhat of a pretext for formalising Osservatorio Sant’Anna. It is a process born out of friendship, informality and reflection on a possible different future for Venice and, specifically, for the church of Sant’Anna.

Your projects actively engage residents by presenting themselves as a transgenerational initiative. What is the curatorial aim, and do you think this model could be a practical way to counteract the “speed” of Venice? I am referring to mass tourism and speculative developments in the world of art and culture.

It is a somewhat intergenerational team, consisting mainly of young people from a variety of disciplines. Lemonot has an architecture studio that does not work strictly in restoration or the construction of new buildings, but rather in performance and public space, ephemeral architecture and the reconsideration of possible uses for existing structures. Maria Eugenia Frizzele is a researcher and PhD student in public policy. My practice and CV are more closely linked to institutional curating. When the group was created, I think the first big decision was to apply “standard” curatorial methodologies, so, for example, to issue press releases. The aims of this methodological approach are both short-term and long-term. For the short term, we have set ourselves the period of concession of the infirmary by the State Property Office – Veneto regional section, owner and manager of the complex. Nine months, from approximately March to November 2025, with the aim of raising awareness of the history of the Sant’Anna complex – which consists not only of the church but also the cloister, the former infirmary and many of the adjacent buildings – about which little is known. Another short-term goal and our primary desire were to establish a temporary, transitory community, involving the local population in particular. This was achieved through the assemblies we convened after the establishment of OSA, made possible thanks to the collaboration of the Pier Fortunato Calvi Comprehensive Institute in via Garibaldi – near the Sant’Anna complex – which granted us the use of the entrance hall, and through the distribution of posters in the district. The public meeting served as a declaration of intent: we are a research group with both an internal and external perspective on Venice, and our goal is to project what the city could be in the long term. We have tried to build networks of proximity and friendships, explaining to the people involved how we would act in this place and how we are acting. By creating shared moments, we have gradually managed to open up more and more of the building, especially through events. This has led to the curation of a cultural programme consisting of social gatherings, small exhibitions, workshops and self-build projects. We have explored the individual spaces, bringing them to life through cultural programming.

And what about the long term?

Since the complex is little known even to the residents of the district, one of our long-term goals is to present a plan that is at once urban-architectural, financial-economic and cultural, so that the entire complex can be rethought. The summary of what we have done is broad and sincere participation, especially in certain events. In my opinion, the main objective we have managed to achieve has been thanks to the questionnaire methodology. In fact, after the first meetings, we distributed questionnaires asking: “What do you imagine for Sant’Anna? What are the needs of this neighbourhood? What services are lacking?”. This enabled us to gain a much better understanding of the needs and desires of the population and, as far as the short-term objective is concerned, also the requirements from an architectural point of view.

Your project revolves around the architectural, social, historical and cultural revaluation of a building. Why this space and how did you obtain the concession?

From an operational and bureaucratic point of view, the process was as follows. We used a non-profit cultural association called Marche Arteviva, of which I am president and with which I carry out other projects. This was because a legal entity or organisation is required to apply for a concession for a site from the State Property Office. Following a request for a concession for research and cultural programming purposes, the concession was granted to the association for a period between March and November 2025, for research purposes, with minimal financial compensation to cover the bureaucratic work involved. It should be noted that the only part of the entire complex that is currently safe to use is the former infirmary: a building adjacent to the church that is not technically accessible at present, but for which the State Property Office has allocated a significant amount of money for restoration, investing in cleaning and potential refurbishment. The concession concerned only the infirmary, but it includes the possibility of using the other open spaces. Another part of the concession aimed to reveal the entire complex, which has been closed for over forty years and has undergone many transformations. Since the 19th century, it has no longer been a church but has become a complex with a military hospital. The place where we reside is called the infirmary precisely because the infirmary was one of the last activities to close, and many elderly people in the neighbourhood remember and recognise that space. On one hand, there is the symbolic idea of reopening at least one door to declare a presence; on the other, there is the possibility of having an operational base from which to work. Today we are collaborating with over fifteen research institutions, including Italian and foreign universities, and many universities are asking to collaborate. However poor it may be, we need a place. This is a cold place, with no electricity or water connections due to the problems of usability of all the buildings around it, but it is a base. We chose it essentially out of necessity as the only place that could be occupied, but after November 2025, when these months of concession expire, a period of negotiation and dialogue will begin with the State Property Office, which, as the owner, will have to decide what it wants to do with this property.

So what does the future hold for Osservatorio Sant’Anna?

The day after tomorrow (17 November 2025, date of the Osservatorio Sant’Anna’s speech in the Speakers’ Corner of the 2025 Architecture Biennale, editor’s note) there will be a meeting to understand what future and what planning to implement. If it were possible to extend the concession, we would need another six to twelve months to finalise a detailed plan: a financial and architectural regeneration plan that cannot be implemented alone. This plan should be a joint effort with the State Property Agency, to study the building’s statics and calculate the total cost of the intervention. From next week, after the closure of the 2025 Architecture Biennale, a period of negotiation will begin. This is a utopian project, the most utopian project I am working on. It is utopian because it could collapse tomorrow morning. A friend said something very nice to me the other night: “I like the project because it is anachronistic, because it works on a place that our generation no longer needs. You are investing in failure, because it is a project with a very high failure rate”. What interests me is the risk of investing not in something certain, but in a very possible failure. I think this could open a curatorial practice of imagination.

Would you be satisfied even if this project were to fail?

Yes, I am already satisfied because a core group of citizens has grown even larger, and this group will be an essential and privileged interlocutor, both for the State Property Office and for anyone who wants to make an investment in the property, even for speculative purposes. It is not an abandoned property that no one takes care of: today it is increasingly being rediscovered and recognised, it is a property where people stop and ask what you are doing. This has created a discussion, a political community – politics in the sense of taking care of the good of the polis – which will have to be taken into consideration in any type of negotiation. From a curatorial point of view, I am satisfied because I believe in this cultural project, I strongly believe in relational economic networks and in the possibility of doing a lot with little investment capital, but with other capital of symbolic human value. My main happiness is what I have described to you: building a voice that must be taken into consideration. A voice to be listened to, which has grown during this period, limits the possibility of failure.

What percentage would you give this failure?

Currently, one of the factors increasing the rate of variability is the search for capital for restoration. Internally, long-term planning is financially sustainable, but it remains a problem. We are asking the State to take charge of the restoration – of the building – while we will take care of the contents, even in the long term. The State should initiate a restoration that is symbolic, then not functional for a hotel but for a community centre and service distribution centre. For my part, my aim is to put the institutions’ backs against the wall: “Do you want to give Venice a symbol and a change of direction, in terms of how Venice is seen, how Venice is exploited and consumed? Now there is a public opportunity to do so, thanks to the interlocutors. Especially in a space like Venice, which, for physical and spatial reasons, cannot expand. Every square metre is important, and there are many here. Do you want to do it or not?”

THE PROJECTS OF OSSERVATORIO SANT’ANNA AND CONVIVIAL PRACTICE

Conviviality is the cornerstone of your projects. I would like to mention two in particular that use food as a means to enrich and unite the community: Laguna nel pozzo, with the participation of artist Andrea d’Amore, and Acquolina, a neighbourhood meatball recipe book. These are two different projects: the first is a performance lunch, the second a publication. My point of view is that of a spectator and user in both cases. What is yours as organiser and curator?

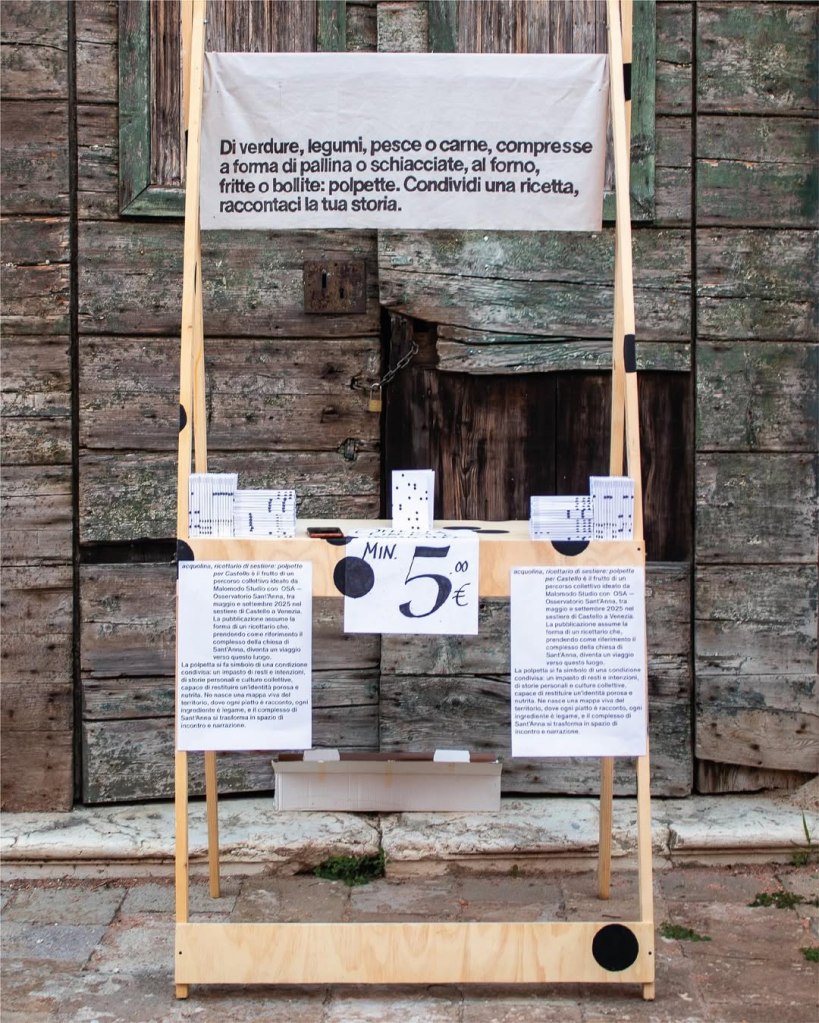

The conviviality of food has been the driving force behind this project from the very beginning. We thought about food and its potential for conviviality, community building and even Italianness, and this intention gave rise to two different projects. The longer-term one is the neighbourhood meatball recipe book, which the Malomodo studio artistic collective – based in the neighbourhood, in front of the church – spontaneously asked to join, proposing to use the spaces to develop a project. We raised a minimal budget to produce both the publication and the project, making the spaces available. It made perfect sense: neighbours with great ideas but no capital or location. This project is based on collaboration: Malomodo first collected a series of recipes, analysing how people live in the social housing of Sant’Anna. Around the complex, they cook meatballs, vegetables, fish and much more, and so the idea of a community meatball restaurant was born. They then asked – and in my opinion this is the winning element of the project – each of the participants to cook their own meatballs and not to eat them alone at home, but to eat them collectively at a dinner party.

And what about Laguna nel pozzo?

The most recent project was Laguna nel pozzo with Andrea d’Amore. Andrea d’Amore is an artist who has been working on conviviality for over twenty years now. I have collaborated with Andrea many times and he is an artist I greatly admire, who does not belong in the slightest to the traditionally recognised art world. He works more on processes than on products, but, above all, Andrea is a person who manages to capture the energy of the places in which he works through the practice of listening. From there, he began to think that one of the most consumed items in Venice is the tramezzino, so he started to build tramezzini using the engineering system of Venetian stilt houses. He created multilevel tramezzini and then, ironically, launched a competition that we would now like to hold every year: the longest tramezzino in Italy. On 14 September, there was a lunch where part of the convivial moment was organised by the artist, but another part had to be assembled and constructed by the citizens. Since Sant’Anna does not have a kitchen, the San Pietro committee – organiser of the San Pietro di Castello festival – provided kitchens and equipment free of charge. After preparing lunch in the kitchens of San Pietro, we transported everything to the cloister of Sant’Anna, organising an event that consisted partly of distributing food – which was served – and partly of something else entirely. The goal was to bring people together and have them work together to create a culinary product to be shared. So, we saw the participants engage in an effort that, although minimal and symbolic, showed their participation, their “taking part of something”.

Which project, in your opinion, has been the most “representative” for Osservatorio Sant’Anna so far? Or, in any case, which one are you most attached to?

There is no main event compared to the others, even from a budget investment point of view. One of the two events I am most attached to, precisely because of this idea of “building something together”, is Laboratori di autocostruzione with Officina Marghera. Reusing materials recovered from the Biennale’s waste, we set up a central table – a model that can be dismantled and used as a parliament – and the circular table we use inside the infirmary. I am fond of this project because it was a practice that involved many people. The other is Laguna nel pozzo.

The practice of conviviality is somewhat of a return to that folkloric and ritualistic sense of community of “gathering” around a table or a space, with everyone “bringing something”. How much do you think this art form can find a place in the art world?

Osservatorio Sant’Anna operates outside the classist boundaries based on the circulation of financial capital or on a system of institutional recognition, the financialisation of works through galleries and buying and selling, collecting or speculation. In this project, we are outside this art world, and we are also pleasantly enthusiastic about being outside it. On the one hand, we need to define what “the art world” means; on the other hand, I think it is necessary, in the words of Alighiero Boetti, to “bring the world into the world”. What does this mean? For me, generating a new world is a curatorial practice and, in this case, it is a continuous negotiation of reality. Not with the idea of having to change it totally through different systems and/or performatively accept it, but rather to negotiate. There was a reality before we arrived, and we are negotiating this reality daily, through activities, presences, people, to bring the world into the world.

How genuine is this negotiation?

I feel that the authenticity is total. As written on the manifesto, it is an act of love towards Venice and brings to light a discourse linked to excess. For me, that building is something that exceeds, beyond any logic accepted by today’s system, and a project like this is an excess in terms of a way of thinking. Obviously, the project for that church is tourist accommodation or an exhibition space connected to large exhibitions. We are trying to turn the complex into a space for the excess of people too, who are often expelled from a political and dialogue context. Sant’Anna is a context that presents very broad problems – the infirmary was used for thirty years for the consumption of heroin and other substances. It is a historically difficult context, where certain types of people have been allocated and expelled. The aim is therefore to bring this monstrosity and surplus to the fore within a discourse, while at the same time creating a surplus of thought. Our policy is that of a theatre-parliament that has a social and political impact, thus building a dialogue and a complex form of polyphony of voices.

THE CURATORIAL APPROACH UNDERLYING OSSERVATORIO SANT’ANNA

How would you define your curatorial approach and that of Osservatorio Sant’Anna? Do you see yourself in this project?

From a curatorial point of view, I have worked extensively in these liminal areas of friction between inside and outside the institutions. These are the areas that interest me most, because they are areas of negotiation, and I find this process very consistent with my personal history. I came to Venice when I was eighteen, studied for three years at Ca’ Foscari and was part of S.a.L.E. DOCKS – a collective that occupies one of the Magazzini del Sale, a space where, together with a group of people, we discussed habitability and the housing problem in Venice, the precariousness of the art world, tourist speculation, ecology and the environment. From a certain point of view, with Osservatorio Sant’Anna, it is as if I have returned to the beginning of my journey of thought and study. At the same time, I have returned to a totally changed environment: in the meantime, I have worked on a major exhibition, a major project such as the 2020 Quadriennale d’arte; I have coordinated exhibitions and catalogues at Macro (Museum of Contemporary Art Rome). I think both were projects that brought new perspectives and points of view to the scene, for example in Italian art. I find that one of the main reasons I got involved was that I could be an added value, a different anti-institutional perspective, even within an institution. When I find these nuclei of thought, of resistance within institutions that seek to broaden the negotiation of language, I throw myself headlong into these types of projects. For me, there is a thread, and Osservatorio Sant’Anna was a way of rethinking and resetting myself, of not necessarily following that flow, of starting over and synthesising everything I have done so far and asking myself how I can rework it. It is a very visceral work: they say that the gut is a second brain. I have chewed it over; now how do I regurgitate it?

Rebecca Canavesi