We met Kyle Meyer during a studio visit organized by the School for Curatorial Studies in Venice, where he introduced us to his distinctive practice. Some time ago, he decided to move to Venice, selling his studio in the United States and leaving behind the bustle of New York, to begin a new chapter in both his personal and professional life. In this interview, we talked about the motivations behind his move to Venice, his future plans and ideas here, the role of textiles, as well as his perspective on curatorship of his works.

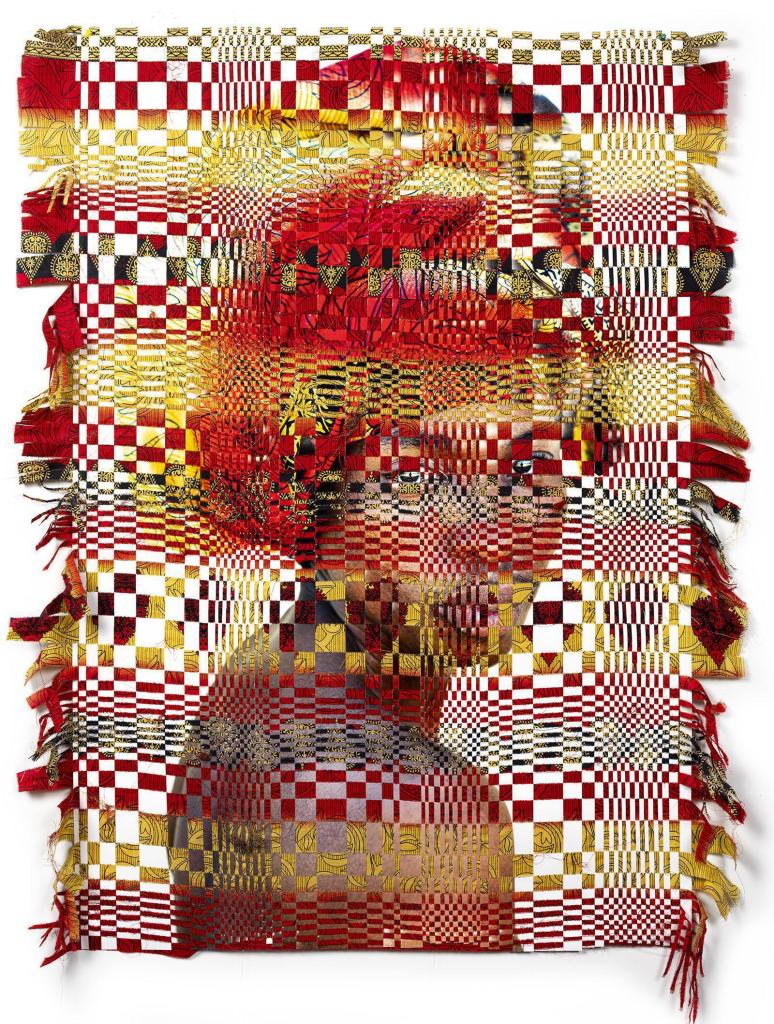

Kyle Meyer (Ohio, 1985) is an American artist whose work sits at the intersection of photography and textiles. In his practice, he questions the potential of photography, born from mechanical and computerized processes, and examines how it still can create human connections by integrating handicraft such as weaving, dyeing, and layering. Meyer learnt weaving while living and working at a basket weaving factory in Swaziland, where he came after his college graduation. The merger of photography and textiles brings both textured and haptic quality into his work, touching such topics like identity, gender, memory, loss, and seclusion. His practice is especially shaped by his identity as a gay man as well as his relationship to LGBTQ+ communities.

His series Interwoven is being shown until 2 November 2025 in the exhibition Rupture and Repair in Morris Museum, New Jersey. His other big projects include Impermanent Skin, 95 Bedford and Bleeding Out.

THE INTERVIEW WITH KYLE MEYER

Now that you’re back in the US for a while, what initially drew you to move to Italy, and why Venice in particular?

First, I moved to Milan at the end of October 2024, and I was there for about a month and a half. I really couldn’t connect with the city at all. It was like a smaller New York, but I didn’t feel the drive to make anything there; I wasn’t inspired at all. Then I went to the Venice Biennale, and it was the first time I did it by myself, so I wasn’t on anyone’s agenda. I really allowed myself to be present for the first time in a very long time and connect to the city. I remember I went to San Giorgio Maggiore and visited Berlinde De Bruyckere’s show there. I was thinking a lot about these works, my creations, and the space. And I really put myself into thinking about what I would be making here and then just said, “Wow maybe I should just move here”. I left that space so inspired by the work that I was almost in tears. I was about to turn 40 and had left the United States – it was time to take control of what I want to do, and not what other people want me to do.

So it was a turning point for you.

Yes. My career was super successful, but it used to be, “you gotta make, you gotta make”. For the majority of my life, I’ve thought about what other people think and not about myself. I’m also always thinking about the art and how the art is placed in a context, so I am allowing the art to kind of dictate my life. I understood I had to really take control over it. Many things just started going in my head at that point. I went back to Milan, and when I came back to Venice a couple of weeks later, everything had changed. The people were gone and it felt very secluded. You could really get lost in that mentality, which I am drawn to. For several weeks I kept coming and went to all the churches and independent spaces like Spazio Punch and SPARC*, which is a big artist and communal space in Venice. People and artists were coming together and showing their work, and I understood this was what I was looking for – a place where I can get completely lost and meet so many beautiful people making incredible things and discussing ideas. And so, at that point in December, I said “I will move here”. It was the first time where I was starting my life over.

At that time, did you feel tired of New York?

New York is a tough place. You have to continuously be making. You have to make money. And the art world is really fucked up in the sense that one day you’re in and the next day you could be out. It’s a constant race, and there’s never ever a chance to fully enjoy what you’re doing. Interwoven took a lot of energy and had taken over my life. I was experimenting and doing other projects, but was not able to fully engage with them and engage in what I wanted to. I got really burnt out and tired. I needed to start making other work. I was dyeing and thinking about how I could use photographic materiality in a different way, and about textiles and color. And the most important thing is: in New York, the idea of being present is quite difficult. Everything is happening at once. I feel very grounded in Venice because it’s not so much chaos. There is chaos within Venice, but it’s not an inundation of chaos all the time. You can disappear.

THE ARTISTIC PRACTICE OF KYLE MEYER

During the studio visit, you mentioned that you no longer work with a gallery. How has your practice changed since parting ways?

I feel free in the work that I’m making because all the work is being made for me. It’s not for the commercial setting or shows. I have been looking at work and putting the puzzle together, but it was kind of all over the place. Since I got to Venice, I’ve had the time to step back and think deeply about what the work is ‒ or was at that time ‒ which is really beautiful. And if I had a gallery, I wouldn’t have been able to do that. I’m in a really deep reflection period, and the work will probably change wildly when I get back to Venice now.

Are there any ideas or projects you want to realize particularly here in Venice?

I’m really interested in the lagoon. A lot of my work is all about imprintation and dyeing of spaces, objects, and humans, which takes a lot of time and is always very precarious. It is also getting that very decisive moment in kind of a chaotic situation, where I have a person to lay down for 30 minutes, which is quite difficult. The lagoon has so much ‒ hundreds and hundreds of years of people coming and going. We’re in a time now where Venice is overrun with people, but the marks that these people have left over the centuries are becoming even more relevant with every step that they take. Just brushing up against the walls takes away and rots away the city. So, it’s getting those imprintations of the city. I also think about the water systems a lot, so I’ll start using the canal water in some way. I am interested in how that water is going to interact with the things that I’m doing, and with the objects that I’m going to be using that will explain consumerism and capitalism within Venice.

I also want to go out into the lagoon and find abandoned boats and things that are discarded there. It’s such a protected place, yet it has things that are left behind or things that are brought from the ocean. So there are definitely ideas at this point. Some of them will just be ideas, but other things will come to fruition.

How are you dealing with the city?

When I am making something, I fully immerse myself in a place. Even in Swaziland: I lived there for a long time, trying to understand the issues that people have. I was sitting, listening and understanding people, or at least I was getting an understanding from an outsider’s perspective. So that’s the same with Venice. I’m coming in as an outsider and I need to understand exactly what the place is doing to me and what it’s doing to other people. Then I can really start making work that I’m excited about. I want the work that I’m making to be very genuine and very thought out. The questions that I’m searching for feel deeply rooted in and intensely connected to the place.

THE TECHNIQUES USED BY KYLE MEYER

When you were living in Eswatini, you learned weaving while still working primarily with photography. This is how your Interwoven series was born, combining imprinting, weaving, and photography. How would you describe your practice today – is there a particular medium or process that now dominates your work?

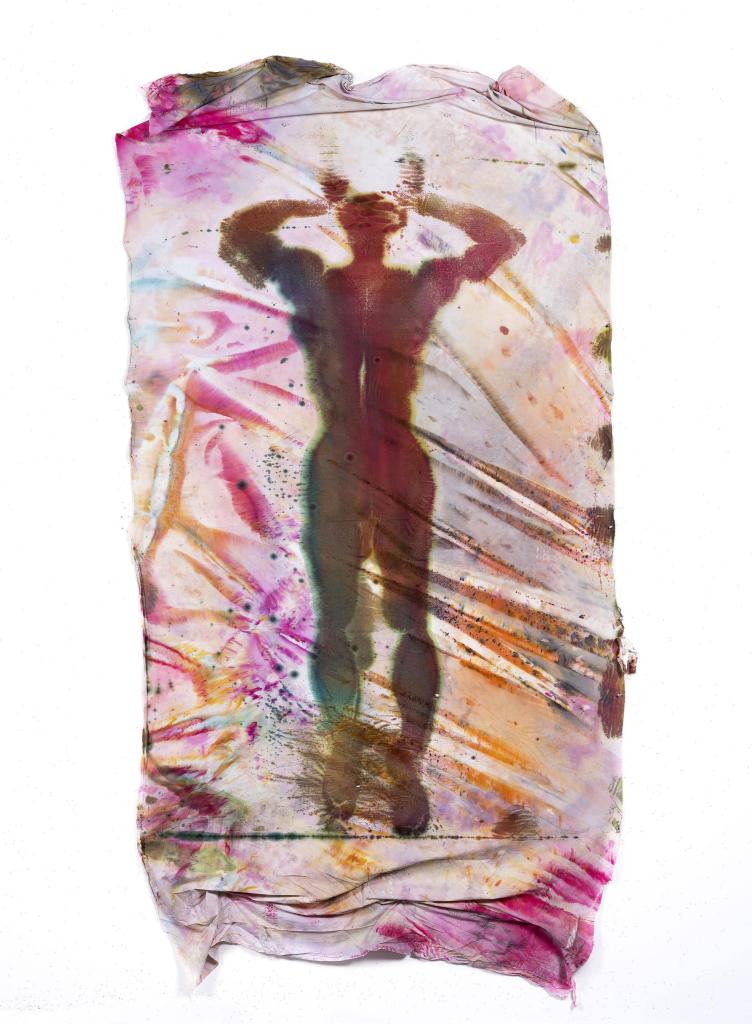

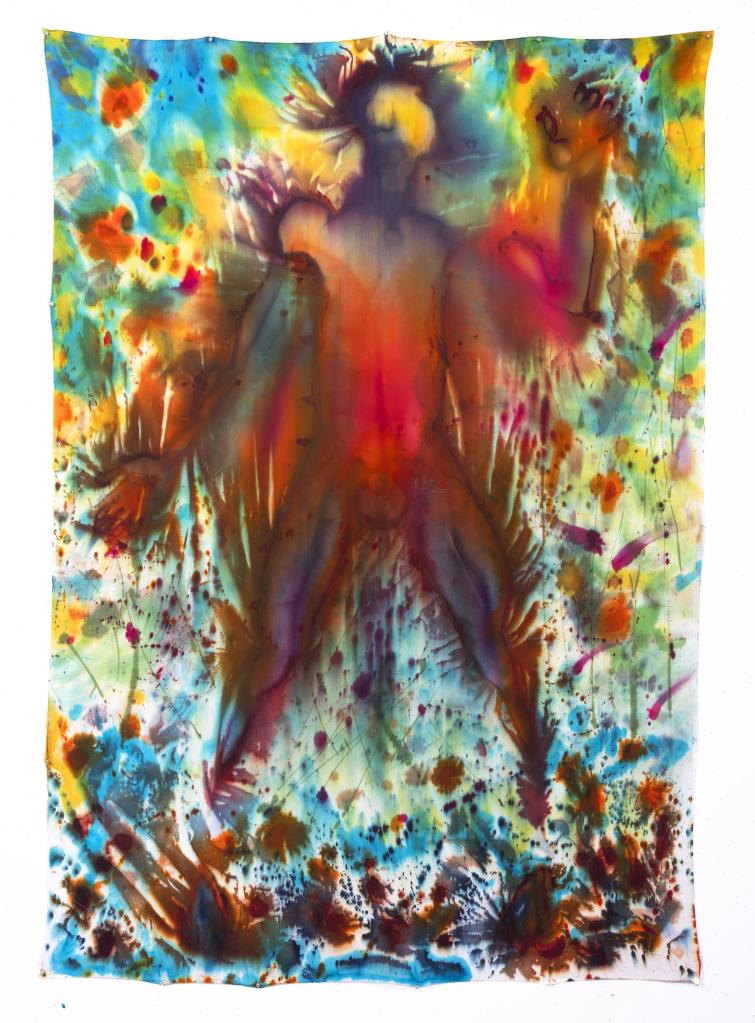

I would say right now my practice is the process of dyeing and weaving. There’s also a very labor-intensive component to my work. Digital photography is ubiquitous now. Everyone with a phone can just take a picture. So what is the authenticity of a photo when it’s all done by a computer? There’s no trace of the hand. Back then I asked myself: “How can I be making photos digitally, but have this component of the handmade?” That’s kind of how I learnt weaving. I was sitting down and listening to people’s stories. It connects you to those people, to the place, to the community. It weaves you together. So I started weaving photos together. Then people were asking me if I thought about making my own textiles. I had dyed a little bit in Eswatini and I thought: “How can I bring this dye into my practice where I’m making my own textiles?” I was experimenting a lot by dyeing the paper with the snow and getting the imprints of leaves and sticks and the environment. Afterwards, I started to use my own body and to dye textiles with it in long-durational performances. Then I did a townhouse (95 Bedford) which was my first real exploration with dyeing a big space. I fully immersed myself in it. I was sleeping there and learning so much about how dyes interact. Sometimes I was throwing pigment and sometimes I was dripping it. Then there was a performance. People were coming in all the time: photographing me, listening to what I was thinking about, and sometimes giving their tips. It was six months of dialogue and I loved it. That is how I understood dyeing is my life.

Later, I was experimenting with how dyes were mixed, but at some point I felt lost. My friend once came over and asked me: “If you could be doing anything, what would it be?” And I understood that I would love to do a human body. I’ve done the structures and objects, but not the human component, which is so critical to my practice because everybody is different. The next day he came over and that was the first time that I did a design of the human body. I think I dyed 40 people or something like that.

Some time ago I did a dyeing on paper. I had never done a work on paper. It had always been a cotton fabric. I had a big roll of paper and thought why not try it. I have to say: this took me to another place in terms of how the work should be made. That was kind of the “Aha moment”. That will be something that, once I get to Venice, requires more exploring and making. It means moving from just dyeing to actually painting these larger pieces from objects and people.

Are those people mostly your friends?

A majority, I would say, are very close friends of mine. But then there’s also people that were complete strangers. It’s a lot of relinquishing control to me, because you’re giving me your body.

How do you usually proceed? Do you begin with a conversation first and then move into the work?

I am never forcing anyone. I’ve never asked anyone if I can dye them. People always ask me to do it. We sit down and have quite a lengthy conversation. It takes around an hour and a half to two and a half hours, depending on how much information is there and where the dialogue is going. But during that, they’re choosing between 12 and 16 colors out of 100. Those colors are tied to specific moments in their lives: joy, a person, or a moment of self-defeat. I just listen to them, but once I have an idea of that specific moment that is kind of critical to them, I ask them to give me a specific color. All people choose in different ways. Then they lay down onto the fabric. I try to get them as comfortable as possible, but also help them feel very powerful in the moment. I ask them what they want to release. Then I’m dyeing the portrait. I kind of go into a trance when I’m doing it.

How do you feel when people share so many personal things with you?

It’s really beautiful. It can be very intense for some people. Some of them break down, but then other people are so elated. It is quite a powerful experience.

There a lot of exhibitions focusing on textiles right now, for example in Textile Manifeste Zurich or Woven Histories in MoMA in New York. The personal connection that appears through the thread and materiality, and the memories the textiles carry seem to be particularly important. Do you feel that textiles, as a medium, are having a unique impact on the world right now, or even “triggering” it somehow? What is special about this practice that other mediums do not have or cannot do?

It’s finally being recognized as not just craft. If you even look at the Bauhaus, at Annie Albers, she wasn’t allowed to go into painting because she was a woman, so she only could weave. But those weavings are the most powerful out of all of the Bauhaus. So now finally there is this emergence, but a lot of those textile people are women. It is really a woman’s work and a majority of weavers are women. So I think that within the art world, there’s now something that is giving women their place, and it’s not the white cis man getting the place anymore. But it also might just be in fashion right now. But within that spotlight, there’s also so much bad textile work as well.

Can you explain what you mean by “bad”?

It’s when you take textiles and make it a mass-produced item. Again, textile making is a very labor-intensive practice. When I see a textile work that is really good, everything clicks, like with Sheila Hicks or Erin Riley, whose works are really incredible. They’re doing it all by hand. That’s really powerful, beautiful work, where you can see the labor and how the material is being used. They’re not just doing it because it’s in fashion, or because they like the way that it looks. For me, in textile work, you have to have a reason when you use fabric. It is not just because of the aesthetics of it.

KYLE MEYER’S PERSPECTIVE ON CURATORSHIP

There are so many aspects that you mentioned: It is a personal medium and requires a lot of labor, so it is a physical and intellectual process at the same time. So, talking about exhibitions and displaying the works, what’s your experience with curators and what do you think is important to consider while exhibiting textiles? Is there something special in comparison to other mediums?

Textile is very powerful, but also textile draws you in. It takes you away from the other things. It’s usually very colorful and very plush. People want to touch it. In displaying textiles, all of mine have very specific ways they need to be hung. For example, all of the Interwoven work is framed. I don’t like showing it unframed, but at the Morris Museum show right now, they have four works that are unframed.

Why is it important for you to frame them?

I don’t want people touching them. It’s about preservation, but also the framing puts it in a completely different context. It really makes it like a jewel in this box. If you’re walking by an unframed work, just that presence of the human is going to manipulate it in some way, and I don’t want that. Those works are very precious because they’re precious people. They need to be put into a jewel case to give them that space and also recognition at some point.

Though where the body works, they should just be pinned to the wall, because it is the physical skin of them. They’re not permanent – they will fade over time. They will change like skin or like a person. So, they don’t need to be in a box. Every little mark is a mark of history. I want the interaction with the environment to change them. In 10 years, one is completely falling apart and things have gotten ripped. That’s okay, because that’s the life of the work. So it really depends on my work, the context of the show, the context of the space. But yes, the curator has their own vision, and you kind of have to go with that. Sometimes you agree and sometimes you disagree, but as an artist, you should always be able to compromise at some point. Every moment that I can get to show my work and get to talk about my work and make people think a little bit differently: that’s the most beautiful. “How can I change a little perspective in some way?” It’s even changing me. I make something and I’m like: “Whoa, I was not expecting that”. I’m just very grateful.

Iuliia Kulikova