In this conversation, artist and performer Marta Magini explores oscillation as both a poetic and physical key to her practice. Through an interdisciplinary approach that weaves together design, visual arts, and performance, she investigates the thresholds between movement and stillness, making visible what usually remains at the margins of perception.

When our body cannot find a stable balance, it makes an almost imperceptible movement, the oscillation. It isn’t necessarily a sign of weakness or confusion. In fact, its very ambiguity is what makes it so compelling. It can signal the uncertainty that comes before a decision, but also the return to calm after an effort. Think of Sylvia Plath’s fig tree metaphor: Esther Greenwood sits between two branches, and each fig represents a possible life. But lingering too long among the options can become paralysis. Oscillating between equally desirable alternatives though only one may truly resonate. “Do I move or stay still? Do I do it or not?”. Yet oscillation is also what happens afterward: when the wave quiets, a direction is chosen, and balance slowly returns. In its mathematical purity, oscillation is a sine wave that never breaks: it slows, accelerates, continues. Perhaps oscillation is not a doubt to overcome, but a necessary motion. A space to pass through. And perhaps balance isn’t a fixed point, but a moment when we choose to go along with the rhythm.

This idea lies at the heart of the practice of Marta Magini (Senigallia, 1995), an artist and performer based in Venice. After studying Design and Visual Arts and completing a Master’s in Performing arts, she developed a research focused on the body and movement, and their relationship to activity and inactivity. We first met Marta during a studio visit while she was a resident at the Bevilacqua La Masa Foundation in Palazzo Carminati in Venice. What struck us immediately was the arrangement of her room: sheets pinned to the wall, metal plates scattered across the table alongside books, and a desk lit by the shy March sunlight filtering through the window. After the effort of climbing the entrance stairs, stepping into that space felt like holding our breath so as not to disturb a fragile atmosphere. We felt the urge to understand more, to ask her about the choices she had made.

THE INTERVIEW WITH MARTA MAGINI

Your path moves across design, visual arts, and performance. How have these shifts shaped your journey over time?

My path has been rather intricate, and at first glance, maybe even chaotic. But in truth, each step, especially in academic settings, was led by a kind of falling in love: with a context, a way of doing things, or an approach to study. It’s as if I’ve gradually fine-tuned my sensitivity to what truly interests me. What’s helped me most is a certain slowness that’s part of my nature (and that I’ve come to appreciate), along with many unconventional cues, decisive clues, and intuitions that prompted detours. Looking back, I see how these transitions, from design to visual arts to performing arts, weren’t ruptures, but shifts, evolutions, and integrations that sparked one another. Moving through such diverse languages and contexts helped develop a perspective that exists between disciplines and looks for connections, even in unfamiliar territory.

What draws you to move between mediums rather than committing to just one?

I feel uneasy relying too strictly on a single discipline. I’m far more interested in the possibility of entering from the side, exiting through the back, placing different knowledges side by side, even fraying the edges in an undisciplined way. I cultivate this expressive freedom with dedication and practice, and I see how precious it is: not just to keep my research alive, but also in working with other artists. In collaborations, and even in performances for other artists, the encounter itself demands openness: toward the other person, their tools, their sensitivity. This kind of relationship gives me space to explore what I don’t yet know, to pursue things I wouldn’t even allow myself to imagine alone.

Looking back, which concepts marked the beginning of your research?

During my Design studies, I worked a lot with ideas of non-functionality, malfunction, opacity, and repetition. I began to understand how important bodies are in the world of design. These were elements somewhat out of place in that academic context, but they started shaping my vision. From there, a thesis in Aesthetics on blurriness led me to Iuav to study art theory and history. At the same time, I continued training in dance and performance practices. Over time, the two paths started informing and contaminating one another.

THE TOPICS OF MAGINI’S WORK

When did you begin working with the idea of oscillation?

About three years ago, though I’d say the interest had been forming long before. One day, replying to a message, I realized that for weeks I had been answering “how are you?” with “like a swing”. That recurring phrase, rooted in something personal, opened up a wider reflection. A particular way of observing emotional states (not only my own), but more importantly, bodies, their movements, and the relationship between activity and inactivity began to take shape. That phrase turned out to be a clue. Since then, oscillation has become a recurring theme in my work as a way of being in the world, a condition of the body and mind, a way of moving through time.

What fascinates you about this oscillating state?

I’m drawn to the underlying ambiguity that every form of swaying carries or generates. Within it lie pause, suspension, relaxation, pleasure, joy, play, life but also waiting, boredom, fatigue, discomfort, obsession, burnout, and death. A child swings in the arms of an adult, the adult rocks the child, and the hanged man sways too. There’s sweetness, and also obsession. Obsession, and also sweetness. Oscillation is both motion and stillness. It’s an incipient movement, a threshold: something that could evolve or come to a halt. An activity that may look like inactivity and vice versa. I’m interested in working within these cracks, where movement is minimal but dense.

How do you explore unproductivity as a value?

Oscillation is also a way of exploring unproductivity as a value. I work with gestures that don’t produce obvious results, that linger in time. I’m drawn to movements that leave subtle marks, to gestures that whisper. I focus on the threshold between movement and stillness ‒ where it’s unclear whether the body is about to move, is coming to a stop, or is simply waiting. That’s where important questions arise: where does the impulse to move come from? When is a gesture useless? How does movement shape our experience of time? For me, there’s something vital in this idea of unproductivity ‒ it allows me to inhabit time differently, to slow it down, or bend it. It’s a time that shimmers, but without spectacle.

How do you conceive repetition in your work?

Repetition has always played a central role, and held deep fascination, not only as a formal tool but as a method. Repeating means crossing through something multiple times, flipping it, circling back, returning. Only then I can reach the surprise ‒ even in what I already know.

THE PROJECTS BY MARTA MAGINI

Your work Luccica segreto was awarded at the 107th Bevilacqua La Masa Collettiva. What is it about?

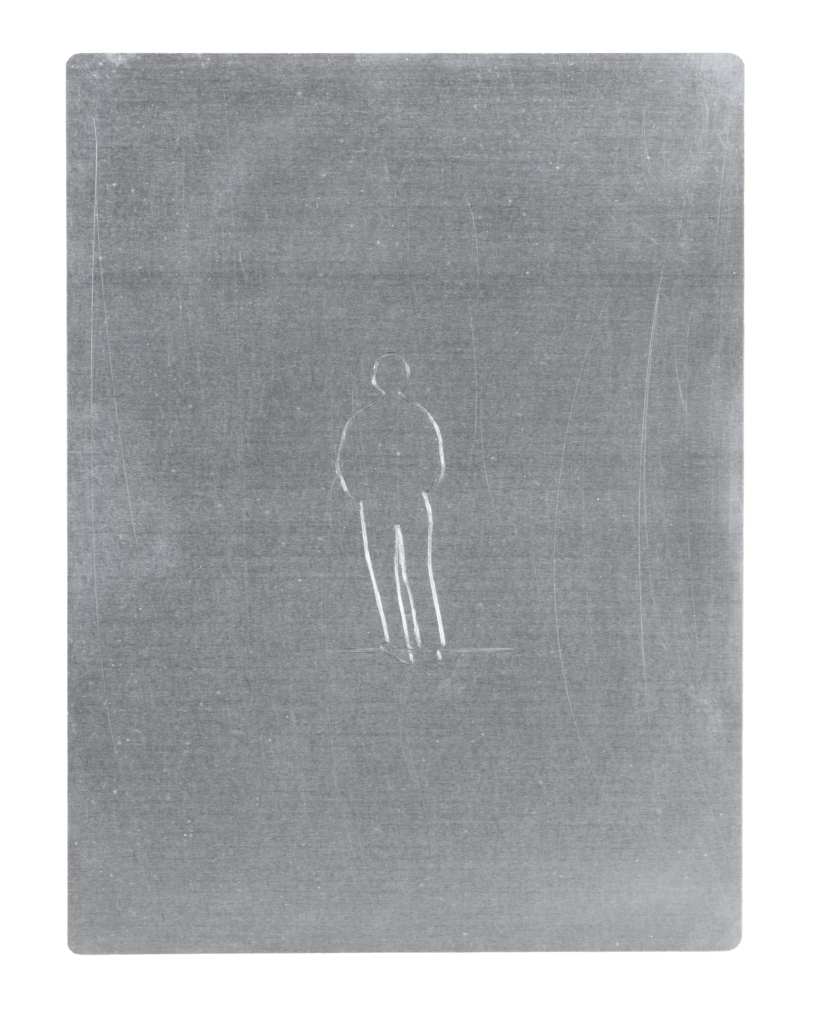

Luccica segreto (movement II in six parts) explores the dynamics of bodies and materials in oscillation: a study of movement as a tension between stability and instability, presence and disappearance. The work consists of six zinc engravings that break down a simple gesture: a body standing upright sways like a metronome. The moment of perfect balance never appears. The piece focuses on subtle shifts and instability. Even the viewer must move in order to see it: your gaze oscillates and enters into a dialogue with the represented body. A fine line under the figure’s feet hints at gravity, a central concept in my work.

In which new directions is your practice evolving?

Right now, I’m diving deeper into drawing, more than I had expected. It’s a practice I’m exploring with both an analytical and highly pared-down approach: tracing, copying, photocopying but never drawing freehand. This method allows me to observe the details of movement and its most delicate implications. I’m also developing a new performance project that builds on what I began with Swinging is like saying no no no (2023). My collaboration with Nicola Di Croce is continuing as well. With Nicola, I always find myself stepping outside my own research, a third space emerges, one that doesn’t belong fully to either of us but works incredibly well. We’ve just started a new piece titled The Skies Are Not Human, inspired by Bohumil Hrabal’s book Too Loud a Solitude.

What role do you imagine for curating in supporting a practice like yours?

To me, curating makes sense when it stems from deep listening. In my experience, I’ve met curators whose sensitivity has played a decisive role: they’ve helped me understand, clarify, even unlock certain aspects of my work. My practice needs time, closeness, silence, and a lot of emptiness. These are fragile but fundamental conditions. I believe this is where curating can be most powerful: becoming a discreet ally, a presence that knows how to hold space for what has yet to emerge.

Linda Rubino