The archive of Bruno Alfieri’s publishing work ‒ free, innovative, and truly independent ‒ is being exhibited for the first time at the Venetian gallery Mare Karina. The exhibition, curated by Chiara Carrera and Mario Lupano, will be open until 12 July 2025.

The exhibition, open until 12 July 2025 at Mare Karina gallery in Venice, could be described as an “open archive”: dedicated to the publishing legacy of Bruno Alfieri (Naples, 1927 – Milan, 2008), it focuses on the period between 1948 and 1973, the year Alfieri Edizioni d’Arte was acquired by Electa. The exhibition presents a collection of books, magazines, and documents from a previously non-existent archive, made possible by the curators’ extensive research and loans from various institutions, including the Giuseppe Marchiori Archive, the Centre for the Study of Visual Arts (CASVA) in Milan, the MART Library, and the Giancarlo Iliprandi Archive.

A critic, curator, and gallerist in the fields of art and architecture, Alfieri was above all a pioneering publisher whose approach to publishing anticipated what we now regard as contemporary: vibrant, communicative, cross-disciplinary, and dynamic. Even advertisements and the colophon were not seen as intrusive elements, but rather as opportunities to reinforce the concept of a hybrid and contemporary magazine ‒ one that could speak to a broader audience by breaking down the rigid separation between “content” and “container” seen in the outdated publications written by intellectuals for other intellectuals. For Alfieri, text, graphic design, and photography were of equal importance, forming a unified whole ‒ a creative, authorial vision behind the editorial project. Through the interplay of visual and textual material, these publications formed conceptual and visual constellations via what he called “the game of juxtaposition”, as explained in the exhibition text. Alfieri’s artistic approach saw publishing as an active agent in the contemporary landscape, capable of proposing ideas, actions, and new relationships ‒ not just as a passive container reacting to what already exists.

PUBLISHING ACCORDING TO BRUNO ALFIERI

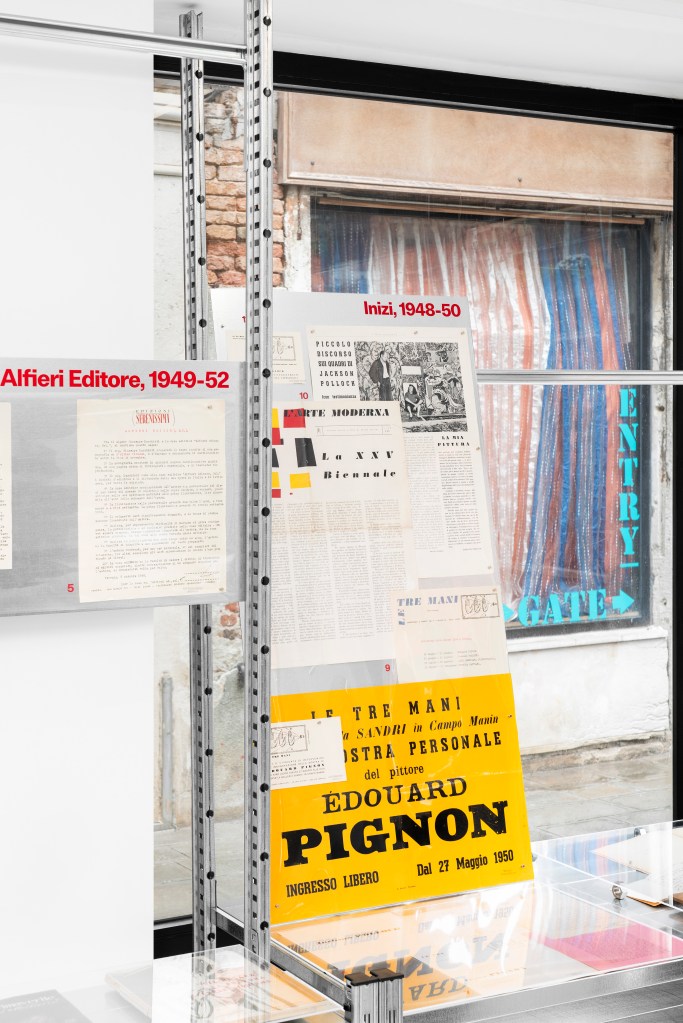

In today’s “image society” ‒ where an obsession with “aesthetic” in the growing world of independent magazines, both digital and print, often masks a lack of content ‒, Alfieri’s attention to form might seem obvious. But in 1948, at the start of his career, this was far from the norm. With the first Italian monograph on Paul Klee, followed by his editorial work for the Venice Biennale catalogues (1951-58) and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Alfieri encountered a rigid, elitist editorial landscape. In a 1949 letter to art historian Giuseppe Marchiori ‒ who would become a close friend and collaborator ‒ he criticised contemporary publishing as “the usual anthology, more or less poorly thrown together, of pompous and inconclusive articles tenuously linked together”. That same letter is now visualised in the exhibition as a “manifesto” of the editor-author’s thinking.

From this frustration, Arte d’Oggi (1949-52) emerged ‒ not as a premeditated project, but as a response to a clear need for renewal. It was, in Alfieri’s words, a beautiful magazine “truly refined, but neither snobbish nor mad”, with an “airy and elegant” design, enjoyable to browse, and offering “a balanced mix of critical essays and informational content”. It was perhaps his background as a bookseller ‒ developed at the Serenissima bookshop founded by his father in 1938 ‒ that shaped his open and dynamic mindset, combining an aesthetic sensibility (viewing the book as a work of art) with a pragmatic understanding of publishing as a business. His books had to be widely distributed and at least bilingual to be commercially viable.

This international vision characterised projects such as Zodiac (1957-63), a renowned trilingual architecture magazine, followed by Lotus (1963-70), now under the Electa group. Alfieri anticipated, by decades, the now essential trend of choosing contributors based not on language but on conceptual and artistic merit. This philosophy also guided the creation of Quadrum (1956-66), a four-language contemporary art journal founded with Belgian publisher Ernst Goldschmidt, which included major figures from various countries on its editorial board.

With Metro (1960-70), his avant-garde magazine largely independent from the art market, Alfieri explored the relationship between text and image, always granting photographers full creative freedom, recognising them as integral to the artistic project.

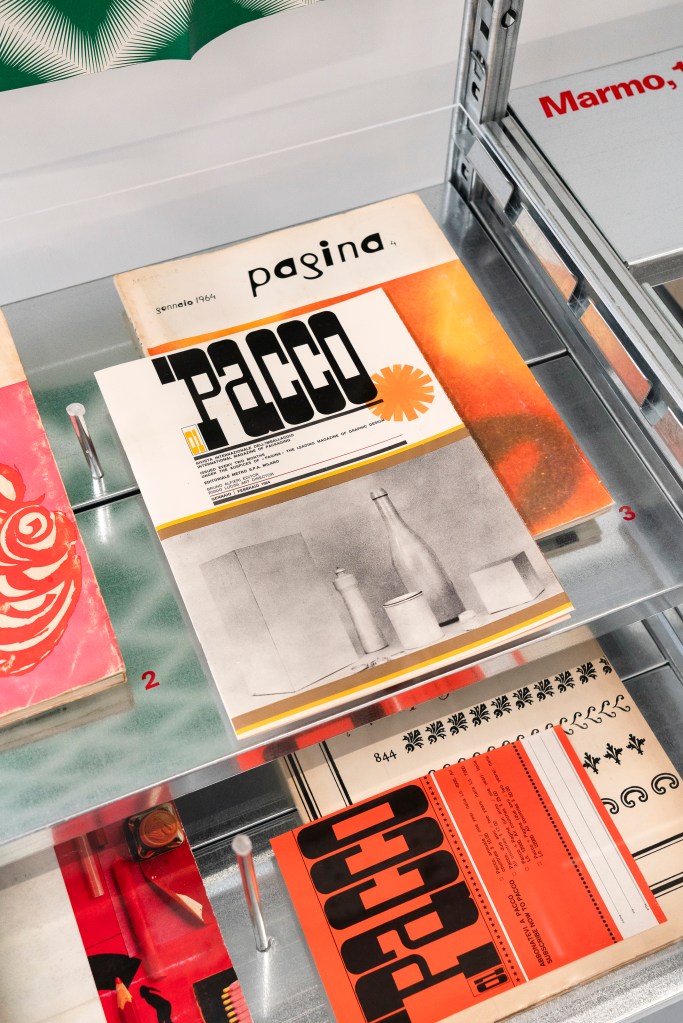

His other magazines ‒ Marmo (1962), Pagina, and Pacco (both 1962) ‒ represented further experiments in form, most notably through the introduction of the “imperfect square” format, which would go on to become highly influential in the field of art and architecture publishing.

THE EXHIBITION ABOUT BRUNO ALFIERI AT MARE KARINA IN VENICE

This vision of a “super-magazine” ‒ a constellation of interlinked elements unified by visual and conceptual coherence ‒ is reflected in the exhibition’s design. Standard metal structures frame the chronological narrative of Alfieri’s work, while still allowing for an open, spontaneous experience. Open magazines, suspended documents, and graphic and textual elements are arranged to evoke the very connections and relationships Alfieri sought to create through his publishing practice.

The art of displaying, as realised by curators Carrera and Lupano, resolves the central paradox of exhibiting archival material: how to present objects that were made to be touched and browsed, yet must now be preserved. By blending the aesthetics of a bookshop with the performative nature of reading, the display itself “leafs through” the archive on behalf of the viewer.

This temporary archive, housed at Mare Karina, is presented with the hope that it may one day become a permanent resource.

Vittoria Morpurgo

Translated with AI

Leave a comment