On the occasion of the group exhibition “Moonkillers”, on display until 15 March 15 2025 at the Tommaso Calabro Gallery in Venice, we asked Alessandro Miotti to describe his poetics of the subconscious and his ambitions.

Alessandro Miotti, born in Sandrigo (VI) in 1991, has graduated in Visual Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, the city where he lives and works. He has participated in various group exhibitions and workshops, both in Italy and abroad, including Salon Palermo 4, at the RizzutoGallery in Palermo, curated by Antonio Grulli and Francesco De Grandi, [ahr-kahyv], (Depa Archive) at the Gustaaf Callierlaan 15, 9000, Ghent, curated by Pieter-Jan De Paepe; Haunted Garden, at The Artist Room Gallery in Soho, curated by Leonardo De Vito, Hôtel-Dieu at the AplusA gallery in Venice, curated in collaboration with the School for Curatorial Studies Venice, and Summer Workshop 2022 by Studio Enrique Martínez Celaya in Los Angeles. He is part of the artist-run collective zolforosso, founded in Venice in 2017. His most recurrent subjects, dogs and cowboys, derive both from artistic tradition and Miotti’s childhood. The painter investigates aspects of the human unconscious through a distorted and original representation of his memories. After a preliminary encounter in his studio in Mestre, we spoke with him in Tommaso Calabro’s gallery in Venice.

AN INTERVIEW WITH ALESSANDRO MIOTTI

Why did you choose the Academy of Fine Arts over going abroad, where the institutions offer more possibilities?

My choice was almost random, so I never considered going out of the country. I certainly didn’t think of attending university. However, knowing that as a child I loved to draw, my mother pushed me towards the Academy. That environment immediately struck me, and since I had stopped drawing during adolescence, I felt the itch of wanting to try again. Then I immediately bonded with friends such as Pierluigi Scandiuzzi, Lorenzo Fasi and Fabiano Vicentini, who gave me great excitement. Professor Di Raco, with his discipline, has provided me with a fundamental approach for my work. On the whole, living the atelier was a huge source of inspiration.

Why did you opt for figurative painting, despite the competitiveness that characterizes this field?

Maybe I’m a bit biased by the luck I’ve had lately, actually I feel that this is a great time to do painting. Even just ten years ago, there were barely any platforms that could make your work stand out and be disclosed on global scale. Of course to be a painter and live from it is surely difficult, regardless of present conditions.

How do you move in the international art scene? Do you have a strategy to present yourself to the institutional environment as well?

I manage my visibility by taking care of my Instagram profile. It is a great way to show the best part of me, which allows me to establish connections with other workers in the sector. I have also expanded my media thanks to figures such as Samuele Visentin, my dealer, and also Antonio Grulli and Tommaso Calabro. A good curator is a key element to bring new art into galleries.

What role does the curator play for you?

Samuele Visentin has touched depths that I wanted and demanded, and for this reason we share heartfelt trust. His sincere and non-judgmental gaze is essential in the fragile moments of creation. He shares the same enthusiasm as me in the creative process and has the ability to visualize my drafts already projected into the future, the same way I imagine them.

Do you think you would be able, together with the curator, to create the right narrative between your works within a solo exhibition? How would you handle it?

I have been wanting to do a solo show for a long time, to build a more reasoned exhibition. I feel that there should be a game of glances between the subjects I deal with, in order to make them interact by creating cross-references between one painting and another, and stimulating the visitor to grasp them. I would probably always stay on the subject of cowboys, but I figure the leitmotifs would be be Sandrigo, the “country boys”, and all the consequences of growing up in the suburbs and then finding yourself living in a city. I would like to express that “factor of deception”, of the closed mentality one grows up with in certain contexts, to later find total openness, and not understanding one’s own way. I would like to name the exhibition Sandrigo or at least refer to it in the title. I would like to convey that sense of belonging to such a peculiar reality, to the people of that place. The dream is to exhibit at the Castle Gallery in Los Angeles, but for now I’d rather to grow through group exhibitions.

THE SUBJECTS CHOSEN BY MIOTTI

What role do dogs play in your works?

My dogs are like self-portraits, animals that are given anthropomorphic connotations, especially in the gaze. However, there is also a meaning linked to the ordinariness, the plain representation of a canine subject: it is generally perceived as cute, but I give it odd expressiveness. The painting with the bone was the first to express this poetics and derives from a bad break-up. I wondered about what I experienced and how to represent the dual figures of the good and bad dog, who fight for an almost heartshaped bone. When I created these narratives, dogs were my first experiment to communicate my issues in relationships, all those psychological patterns.

And what about cowboys?

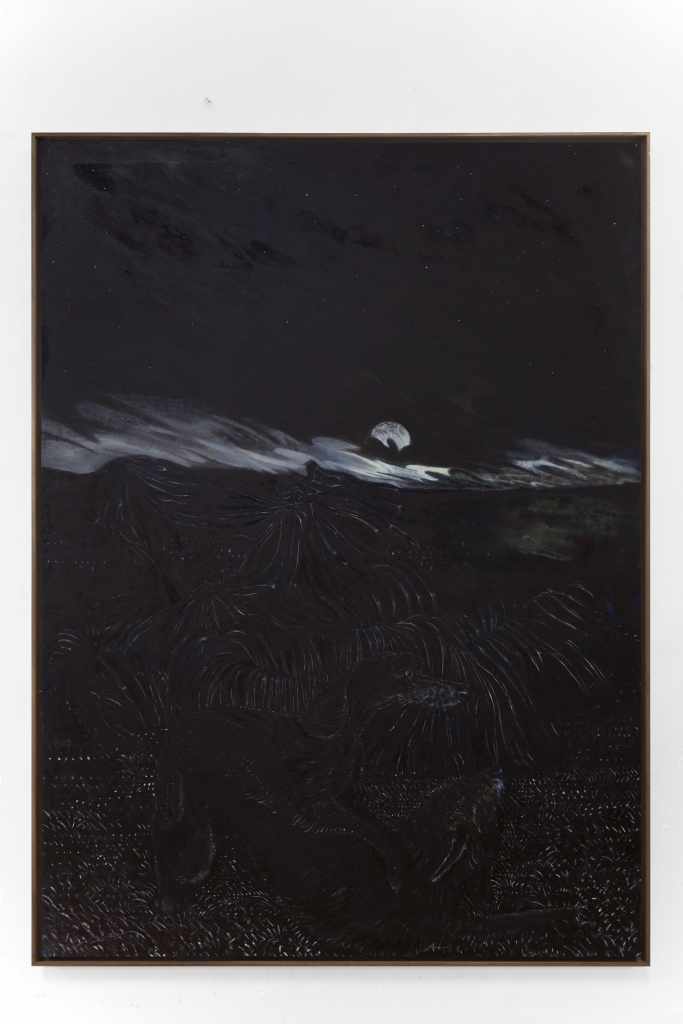

I’ve always felt a constant piling-up of personal things to express, that’s why I feel drawn to this subject: I want to do something that fills my mood and charges me with a sense of revenge, allowing me to take up my space. Cowboys were born during a workshop in America. I did the first ones in the summer, all black and on horseback. This is because at that time I used to live in a black area of Los Angeles, where the inequality was evident. They were therefore born from a first attempt to express the feeling of being different, marginalized, which I then sublimated in the later, more personal works. This year I have been working a lot on loneliness, as I have often had FOMO, especially living in Venice. I wondered how I will die, or rather how a part of me will die: loneliness serves as a space to improve oneself, but it must be faced, not avoided or anesthetized through, for example, addictions.

Your works speak of loneliness but also have an erotic charge. How do you reconcile these two aspects?

As for the relationship between eroticism and loneliness, understood as marginalization, it is more likely to be experienced by the female gender, given our male-dominated society. The erotic element stands precisely as a counterbalance, displayed in the face of insecurity, aimed at masking it by flaunting a fake nonchalance. The “hyper masculine” connotation of my cowboys completely reflects that: all those attitudes which are introjected by males not to face their insecurities and find purpose through dialogue. When hiding behind fake confidence, one inevitably comes up as funny, and is not true first and foremost to themself.

THE PAINTINGS BY ALESSANDRO MIOTTI

How do you organize your day in the studio?

I usually work at night, although really no one likes to work at that time. The atmosphere at night is magical, there is only me, fewer distractions, and when the flow starts, I want to go along with it until the end, until I have energy.

During the studio visit, you described how your paintings are the result of layering materials up to the final touches in oil. What kind of correspondence is there between the creative process and what you feel while painting?

I also prepare myself psychologically to face work, with all the thoughts it entails, the anger of when things don’t turn out the way you want, the idea of doing something criticizable. My work is still born out of frustration, but overlapping multiple layers of paint is also a way to make it clear that at a certain point I no longer care if the result is clean, smooth. I can challenge myself, have second guesses, dramatically change what I’m doing. I mainly start with oil pastels, creating a free drawing on the canvas. The oil pastel is full of potential because there is no external link between the hand and the stroke. The mix also includes acrylic, spray, and finally the oil that is used to finish and give different technical qualities. My goal is to enhance both the freshness of the picture in its initial phase, and the final touch that confers completeness. This way I feel that my paintings enrich the eye, creating a more vivid representation. The work can be observed in its entirety, but also progressively, dwelling on elements depicted in a vaguer way or on others more structured.

Do you think your paintings have the power to spark a reflection?

I hope to send a message, I am excited to know that my works can have an impact on those who see them, that people recognize themselves in them, especially those who do not deal with art. The most important feedback I receive, even in the studio, is from friends who work in completely different fields, who are curious and understand, identify with them. Even my mother manages to grasp something that goes beyond the trivial representation of “smoking joints”, and she gets the energy charge. I aspire to not be inscribed solely in contemporary art, as it happened to Goya: in his paintings there is no formal aspect that dates back to nineteenth-century art, they could have been made yesterday. What makes his work eternal is also the caricatural trait he imprints on the subjects: they are not people who really existed, yet they are real, like my cowboys. My intent is not to totally break with the past, but to create a sense of “revelation” within subjects that are already there.

Giulia Botteri

https://www.instagram.com/miotti_alessandro?igsh=MXVuZm1uNGo4MHpidQ==