What does reenactment mean and what role does it play in contemporary curating? This is one of the many questions underlying the interview with Stefano Mudu, scholar and expert on contemporary art.

After an education in Architecture, Stefano Mudu (Cagliari, 1990) graduated in Visual Arts at the IUAV University of Venice, specialising in contemporary art theory and criticism. Alongside Cecilia Alemani in the research operations for the Biennale Arte 2022, he has edited several publications and independent editorial projects. In this interview, Mudu offers a critical look at contemporary art and its articulated linguistic paths, conducting an investigation that follows the complexity of becoming through the echo of memory.

In your work you have explored the phenomenon of reenactment, understood as an approach to curating. What is reenactment and what is its ultimate goal?

Offering a single definition of the term “reenactment” is complex, especially because in contemporary artistic practices it is often used as an “umbrella” term, capable of indicating any form of reactivation of already existing visual, sound, or performative materials. In my research, I tend to consider reenactment not so much as an aesthetic category but as a genuine critical strategy of the contemporary era. Although practices of reuse, citation, and recontextualization of existing materials have always existed, what changes today is the awareness and intentionality with which these actions are carried out. Since the 2000s, more and more artists, curators, and cultural institutions have begun to reshape episodes from the past ‒ sometimes in a philological way, other times with freer interventions. Many authors, for example, have combined materials and references from different times and contexts, making them coexist and updating them within a new artwork or curatorial device. In general, the ultimate goal is never singular: one may reactivate to commemorate, but also to question; to transmit, but also to transform. Often, reenactment is a tool to critically interrogate the past, overwrite official narratives, and bring to light contradictions, shadow zones, or marginalized stories. What unites these practices is the awareness that no historical narrative is definitive, and that every act of reactivation is also an act of rewriting.

REENACTMENT FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF STEFANO MUDU

Why did you choose reenactment as a practice to investigate?

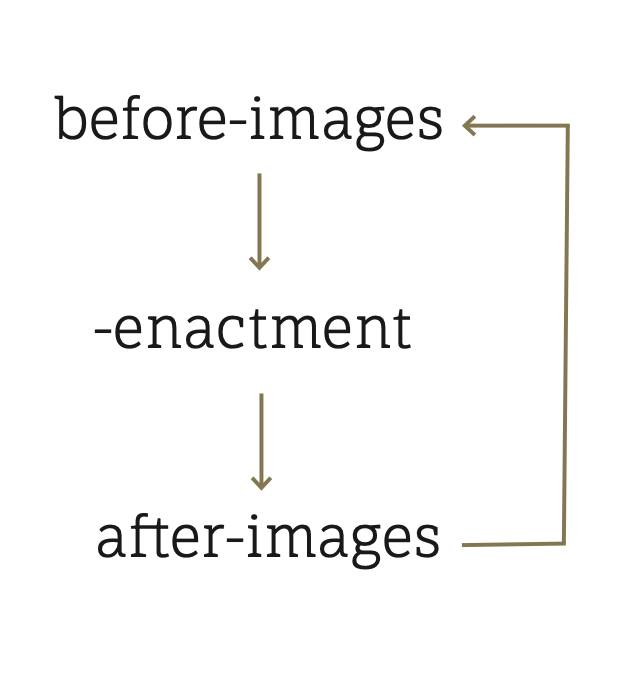

The answer is partly contained in the previous one. My interest in reenactment stems from a critical urgency: to understand, without pretending to offer definitive answers, the origin and meaning of this widespread tendency towards reactivation in the contemporary artistic and curatorial field. When I began to focus on it, in 2018, the term reenactment appeared everywhere: in curatorial texts, press releases, artist portfolios. Yet, its use always seemed different to me ‒ sometimes vague, often ambiguous. As the word circulated, there was a lack of a theoretical and methodological framework to clarify its implications. This lack gave rise to my research. I dedicated my PhD to developing a theoretical model I called the “migratory cycle of images”, an analytical device useful for reading and breaking down reactivation operations into three phases, based on the role played by images. I defined before-images as reference images, that is, those pre-existing materials used as documentary bases to shape a new narrative. With enactment, understood not as a general category but as an intermediate and active phase, I indicated the design and creative moment when the transposition occurs: the point where images are reshaped, not simply replicated.

Finally, I referred to after-images as what remains of these operations: the new works, devices, or narratives that result from a process of reactivation, which in turn are never conclusive, but are potentially destined to become before-images for other future reenactments. This model does not merely describe a phenomenon but is an integral part of my curatorial approach: I always try to interrogate the temporal, archival, and relational dimension of images, challenging the idea of linear originality or unequivocal authorship.

Must reenactment adhere to strict historical conformity? Can it be considered a form of conservation or study of art history?

I would say no, in both cases. Reenactment is markedly different from historical reenactment precisely because it does not aim for a slavish reproduction of the past, nor does it seek to faithfully preserve its formal or conceptual codes. Unlike folkloric reenactments ‒ such as religious processions or traditional dances ‒, which cyclically present established materials, trying not to alter their iconography or structure, reenactment always introduces a variation in repetition. It is precisely this distance, this gap, that makes it interesting.

The result is never a copy but a new, often unprecedented work that maintains a genealogical link with the original reference, while departing from it. This practice challenges established notions such as authorship, authenticity, and uniqueness in contemporary art, redefining the ways in which one can “inhabit” the past.

As already mentioned, although reenactment is connected to the desire to recover memories, archives, and art histories ‒ often marginal or forgotten ‒, its goal is not conservation, but rather critical and transformative. Rather than conserving the history of art, reenactment reactivates, interrogates, and often rewrites it in light of new urgencies, sensibilities, and perspectives. It is, therefore, a form of active and creative study, taking the past as a starting point, not as a constraint.

EXHIBITIONS AND REENACTMENT

A major example of reenactment is When attitudes become form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, the exhibition held in 2013 at Fondazione Prada in Venice, curated by Germano Celant. What do you think of the exhibition and its particular curatorial method?

What is the boundary, in reenactment, between the critical and participatory recovery of historical memory and its transformation into pure spectacle?

The restaging of the historic exhibition curated by Harald Szeemann at the Kunsthalle in Bern in 1969 is now considered a case study in curatorial reenactment. Not only because Germano Celant was among the first to reimagine an entire exhibition episode from the past, but also for the radical way he approached the project. The installation at Fondazione Prada did not merely cite the original show: it physically reconstructed the environment, faithfully replicating the Kunsthalle’s floor, the arrangement of the works, and even marking absences with transparent, almost museographic captions.

However, precisely where philology was not possible or became more uncertain, the operation gained a critical and speculative dimension. The discrepancies between the original and the new version were not concealed but exhibited, transforming the exhibition into a space of friction between past and present. In this sense, Celant’s reenactment was not reduced to a nostalgic or didactic act, but was configured as a reflective device capable of raising questions about curatorial authority, the role of the institution, and the very possibility of “restaging” art history.

Yet there remains a critical issue to consider: to what extent can a reenactment operation maintain a critical and participatory function without sliding into mere spectacle? The risk is that, under the pressure of major cultural institutions, these projects end up flattened into an aesthetic fetishism of the past, transforming historical memory into an object to be contemplated rather than questioned. Finding a balance between historical rigor and contemporary reinvention is perhaps the most delicate ‒ and fascinating ‒ challenge that every reenactment project must confront.

What have been other great examples of reenactment in Italy or Europe?

Keeping in mind that ‒ as mentioned ‒ today the term reenactment can also describe projects that bring together, within the realm of a new work, references from different historical trajectories, there are several curatorial examples that have used anachronism and reactivation as critical methods. In Italy, I think of the exhibition Time is Out of Joint (2018), the reinstallation of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome curated by Cristiana Collu. As the title suggests, the project brought into dialogue works created in different contexts and times to tackle universal themes such as death, love, history, and war. Chronological linearity was suspended, encouraging unprecedented juxtapositions and layers of meaning. Another significant example is Slip of the Tongue (2015), an exhibition hosted at Punta della Dogana in Venice and curated by artist Danh Vo. Here, the artist selected some of his own works ‒already comparable to reenactment for their composite and citation-based nature ‒juxtaposing them with works from even very distant eras. For example, a 15th-century work by Giovanni Bellini dialogued with a 1994 sculpture by Hubert Duprat. The result was an exhibition device capable of creating temporal and semantic short circuits, questioning both the history of art and its exhibition status.

How is the research process structured to reconstruct a historical exhibition?

Reconstructing a historical exhibition is a complex task that entails layered and interdisciplinary research. It usually starts with mapping sources: catalogues, historical photographs, press reviews, correspondence between artists and curators, archival documentation, critical reviews, and, when possible, interviews with protagonists or direct witnesses. It is essential to understand the historical, political, and cultural context in which the exhibition was conceived, as well as the original curatorial vision and the critical reception of the time.

The work is structured along two main axes: on one hand, the philological reconstruction of the material and immaterial elements of the exhibition (works, installation, graphic design, communication); on the other, a critical reading that enhances its present relevance by putting it in dialogue with contemporary issues. Reconstructing a historical exhibition does not mean merely reproducing it faithfully but also problematizing its impact, limitations, and implications.

PROJECTS AND RESEARCH BY STEFANO MUDU

In 2022, you assisted curator Cecilia Alemani in designing the Venice Art Biennale. How was your work structured, and how did you value your contribution?

During the preparation of the 59th Venice Art Biennale, The Milk of Dreams, I had the great opportunity to collaborate with Cecilia Alemani mainly in the phase of research, selection, and analysis of historical sources, with a particular focus on female artists and figures less known or marginalized in the canonical narrative of art history. My work developed in several phases: from compiling an annotated bibliography to identifying works and materials in public and private archives, culminating in supporting the drafting of critical texts for the catalogue and exhibition apparatus.

Perhaps my contribution was in facilitating the curatorial work in constructing a transversal and comparative perspective, contributing to a narrative structured around alternative genealogies and heterogeneous imaginaries. These were, in the end, the “historical capsules” around which the entire expository and conceptual framework of the exhibition revolved.

What insights and inspirations arose from the Biennale experience?

The Biennale experience confirmed to me that every curatorial project, to be truly effective, must begin with profound historical awareness. No exhibition is born in a vacuum: every visual narrative is built on the shoulders of giants and dialogues, knowingly or not, with pre-existing cultural and artistic genealogies. The Milk of Dreams also explicitly referenced the past, not only through the “historical capsules” but in the title itself, which recalls a children’s book by Leonora Carrington. As in the stories of the surrealist artist, the exhibition depicted a world in which bodies and identities are subject to continuous transformations ‒ a powerful metaphor for facing the ecological, social, and technological challenges of the present.

From this experience, I carry with me an even deeper awareness of the potential of marginal artistic narratives: minor, forgotten, or removed stories that can nonetheless be critically reactivated to open up new perspectives. Reinterpreting and sometimes “manipulating” these stories is not only an act of rediscovery but also a way to renew our outlook and stimulate an evolution in curatorial and critical thinking.

Giada Bartolini

https://www.instagram.com/s.mudu/

Translated with AI