In the work of Gražina Subelytė, curating becomes an instrument of discovery, an act of care and, above all, an exercise of active memory. Among forgotten archives and works capable of speaking to the present, her gaze moves carefully between the stories and contexts that have generated them, restoring a living and questioning dimension to art.

Originally from Lithuania and trained between Germany and the United Kingdom, Gražina Subelytė has worked for over seventeen years at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, where she built a strong and passionate curatorial career. After completing her PhD at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, she signed exhibition projects that have renewed the reading of twentieth-century art from Surrealism to esoteric practices, contributing in an original way to restore centrality figures and movements often forgotten. Exhibitions such as Peggy Guggenheim. The Last Dogaressa (2019-2020) and Surrealism and Magic. Enchanted Modernity (2022) highlight her interest in the complexity of the role of curator, understood as a mediation between public and narrative aspect.

This interview comes from an intimate and generous meeting, in which Gražina Subelytė talks about her working method, the formative references and the urgency of rewriting a broader, open and conscious art history.

How did your journey in the art world begin and what led you to work at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice?

I attended the Bachelor’s degree course in Germany, at Jacobs University in Bremen, with a double major in Social and Political Sciences and in History and Theory of Art and Literature. I then obtained a Master’s degree in Modern and Contemporary Art from Christie’s Education in London, in collaboration with the University of Glasgow. I did several internships: from Christie’s in Berlin to the ZKM in Karlsruhe, in a private gallery in London and at a research company on stolen art. I came to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection about seventeen and a half years ago for an internship and, basically, never left. During my experience here, I completed a PhD at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. I must say that I have always been attracted by museum contexts, where art meets the public. I find Peggy Guggenheim a truly inspiring and courageous collector and patron. It is a privilege to work in this museum, which represents an extraordinary crossroads of modern art, research and storytelling.

Are there figures ‒ masters, curators or even artists ‒ that you consider fundamental in what has been your training, even indirectly?

First of all, my art teacher, Povilas Spurgevičius. When I or other students drew and painted in more traditional ways, he always encouraged us to free our imagination and not limit ourselves to what is visible and obvious. He was the one who taught me to create with unlimited imagination. Thanks to him I understood the importance of imagination and later decided to study art history. Indeed, the 20th-century artists represented in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection have really broken with tradition, looking for new ways ‒ often unconventional ‒ to represent not only the outside world, but also their own inner dimension. We always try to emphasize the revolutionary spirit of this collection. Another important figure for me is Professor Ursula Frohne, who was my art history teacher at the university in Germany. She inspired me deeply and taught me a fundamental lesson: all art is political. Speaking of historical figures, I am inspired by the work of legendary avant-garde curators such as Katharine Kuh and Palma Bucarelli, who was director of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome.

THE CURATOR ACCORDING TO GRAŽINA SUBELYTĖ

How has your vision of the role of curator changed over time? What are, in your opinion, today’s responsibilities that this figure should have?

I believe that a curator is a storyteller, a figure who mediates between the work and the audience, but who today also becomes an agent of cultural change. The responsibility of telling plural stories, recovering forgotten voices and offering new looks is central. In addition, especially in an institution like the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, it is essential to show how truly revolutionary was the art that Peggy Guggenheim collected. It is important to maintain a continuous dialogue between past and present.

How do you balance your curatorial vision with the institutional context in which you work and with the public to whom the exhibitions are addressed?

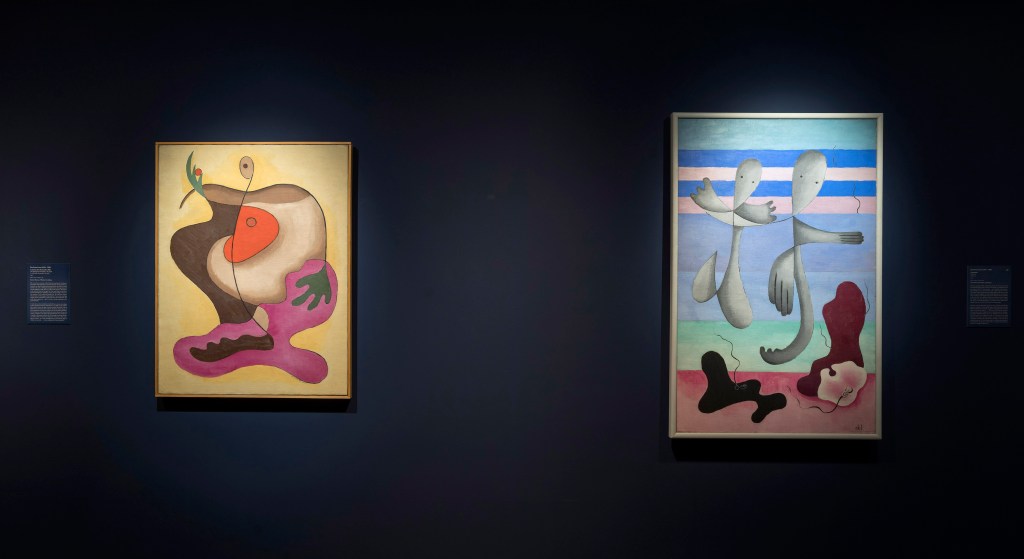

In our exhibition program we always try to find a balance between known names and less known artists, so that the public can also discover new artistic visions. In everything we do, it is fundamental for us to show how the art of the period in which Peggy Guggenheim lived continues to be incredibly current even today, as it presents many similarities with the contemporary world. Now, as in the course of history, humanity is experiencing a period of transformation, driven by social and political developments, technological advances, wars, climate change and other factors that directly or indirectly affect our state of being. This influence is also deeply reflected in art, with works that become real documents capable of telling these revolutionary changes. The 20th century was a time of profound political, social and artistic change. What today, in an apparently paradoxical way, we call classical modernity has advanced thanks to the experimentation and revolution of the very idea of what art can be, finding radical and new ways to represent the inner and outer reality. The artists represented at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection have broken with tradition and challenged the artistic legacies of the past. They have invented new expressive languages, reflecting changing values and conventions. In my work as curator of both the permanent collection and the exhibitions I curate, I always emphasize these aspects.

How do you come up with the idea for an exhibition? What is your approach to research and selection of themes and artists to be presented?

Inspiration for an exhibition can come from many sources, but it’s always about finding something original, something that has never been done before. Each exhibition is born from a question, a curiosity or a void that I feel in the museum story. I study in depth the movements and artists of the twentieth century, but also the exhibitions that Peggy Guggenheim organized during her life, both in her first gallery, the Guggenheim Jeune (1938-1939) in London, and in her museum-gallery Art of This Century in New York (1942-1947). I am always impressed by how much more is to be found out about her support for artists! For example, she has organized truly avant-garde exhibitions, both collective and numerous personal, dedicated to women artists such as Janet Sobel, Irene Rice Pereira, Sonja Sekula and Virginia Admiral, just to name a few.

Most of the artists represented in our collection are unfortunately no longer alive and, in these cases, I read as much as possible, I update on academic research and the latest exhibitions (I talk with colleagues and scholars), always looking for new points of view to get closer to their art. I spend a lot of time researching the works and their presentation ‒ for example, how the artist would like a particular work to be exhibited. However, it is not only about the objects, but also the relationships that surround them: those between artists themselves, with history, with other disciplines… There is always a continuous shift between micro and macro perspectives.

Some of my exhibitions are thematic, others chronological, or a mix of both. The selection of artists or themes is organic. For me, exhibitions are a form of narration: as a curator, I build a story, similar to reading a book. However, if on the one hand the exhibitions must teach and offer answers, on the other they must also test us and make us ask questions.

EXHIBITIONS CURATED BY GRAŽINA SUBELYTĖ

What led you to specialise in an artistic movement such as Surrealism? What do you still find relevant or fascinating in this movement?

Peggy Guggenheim was one of the most important patrons and collectors of Surrealism worldwide. She understood that Surrealism was an extremely current movement, and I fully share this vision. I remember the words of the artist Remedios Varo. When asked if Surrealism was in decline, she replied: “I don’t think it can ever disappear in its essence, because it is inseparable from humanity”. The surrealists undoubtedly predicted the times we are living in: they were pacifists, anti-capitalists, anti-colonialists, promoting love for nature and ecology, and the surrealist artists were strong and conscious proto-feminists. Faced with the absurdity of the reality of the two world conflicts, the surrealists turned to dreams, the unconscious and magic to look for alternative ways of understanding the universe. One hundred years later, we find many similarities with our present ‒ from pandemic anxiety to climate catastrophes, and of course wars. I believe that society has begun to recognise the importance of this movement, which is often misunderstood. The surrealists believed deeply ‒ albeit idealistically ‒ that they could influence the world, to “enchant it again” in a moment of collective trauma. Surrealism is a philosophy of life that chooses a positive look on the world to renew it through self-knowledge. I believe that each of us can draw inspiration.

During your lecture at the School for Curatorial Studies Venice, you told us about the exhibition dedicated to Peggy Guggenheim’s first gallery, the Guggenheim Jeune, which will be presented in Venice and later at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. What challenges do you encounter in telling a figure like Peggy Guggenheim in a British context, compared to Venice and New York?

The main challenge is to contextualize Peggy Guggenheim, always keeping intact her uniqueness and complexity. In each context, we present to the public the many roles that she has held: collector and patron of the arts, promoter of avant-gardes, cosmopolitan figure. For us, this exhibition is an opportunity to explore a lesser-known phase of her life.

In your exhibitions there is often a special focus on female artists, especially those who are forgotten and marginalized. How do you carry out your research work in this case? What is the criterion for selecting artists?

A fundamental criterion in the selection of artists was not that they were women, but that they were great artists, capable of producing works of high quality and deserving to be better known by society.

CURATORSHIP AND RESPONSIBILITY

Do you think that the curator’s role can have a real impact in rewriting more inclusive art history? And how do you try to do this in your daily work?

Yes, I believe that the curator has a concrete responsibility in this regard. The way we tell art ‒who we include, what works we value ‒ builds imaginaries. In my daily work I always try to ask myself what is missing, who has been excluded and why. Inclusiveness is not only a matter of representation, but also of critical perspective.

What advice would you give to young curators trying to make their way in this working environment?

I would suggest to be curious, rigorous, devoted and patient. I believe this is true in any field: it is essential to really commit to the chosen path. If you are passionate about what you do, don’t be afraid to show it. Be patient: things take time and nothing significant comes immediately. It is important to study a lot, visit exhibitions, read, but also know how to listen and talk with others. Finding your own voice, an authentic point of view that guides the work, is essential. And finally: do not be discouraged. There is no shortage of difficulties, but passion and dedication really make the difference.

Valeria Eneide

https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/it/

Translated with AI