For a long time, the white cube has been considered the ideal space for contemporary art: neutral, silent, isolated from the world. Decades later, this exhibition system not only appears outdated, but has been called into question by a radical evidence: there is no aesthetic experience that is not situated, corporeal, influenced by its historical and cultural context.

The white cube is an exhibition model that became established after World War II, characterized by white walls and uniform lighting, designed to present the work as autonomous and timeless. Research in the field of neuroaesthetics — in the wake of the discipline pioneered by neurobiologist Semir Zeki — has shown that aesthetic judgment is not formed in a pure mental space, but emerges from the interaction between environment, body, cognitive expectations, memories, and reminiscences. Recent studies show that the exhibition context significantly influences the perception and evaluation of a work, modifying neurophysiological parameters such as brain activity, heart rate, and eye movements. In other words, what we see is never truly separable from where we see it. BrainSigns — a spin-off of La Sapienza University in Rome since 2010 — uses neuroscience to analyze brain and physiological signals, producing value in the field of neuroaesthetics. Neuroaesthetic experiments are usually conducted in unconventional exhibition contexts. Research has shown, for example, that identical works can be evaluated significantly differently depending on where they are presented or the preliminary information provided to visitors. Among these, the attribution of authorship plays a meaningful role: it has emerged that prior knowledge of authorship — whether human or artificial intelligence — has a decisive influence on the final aesthetic judgment.

NEW CURATORIAL PRACTICES

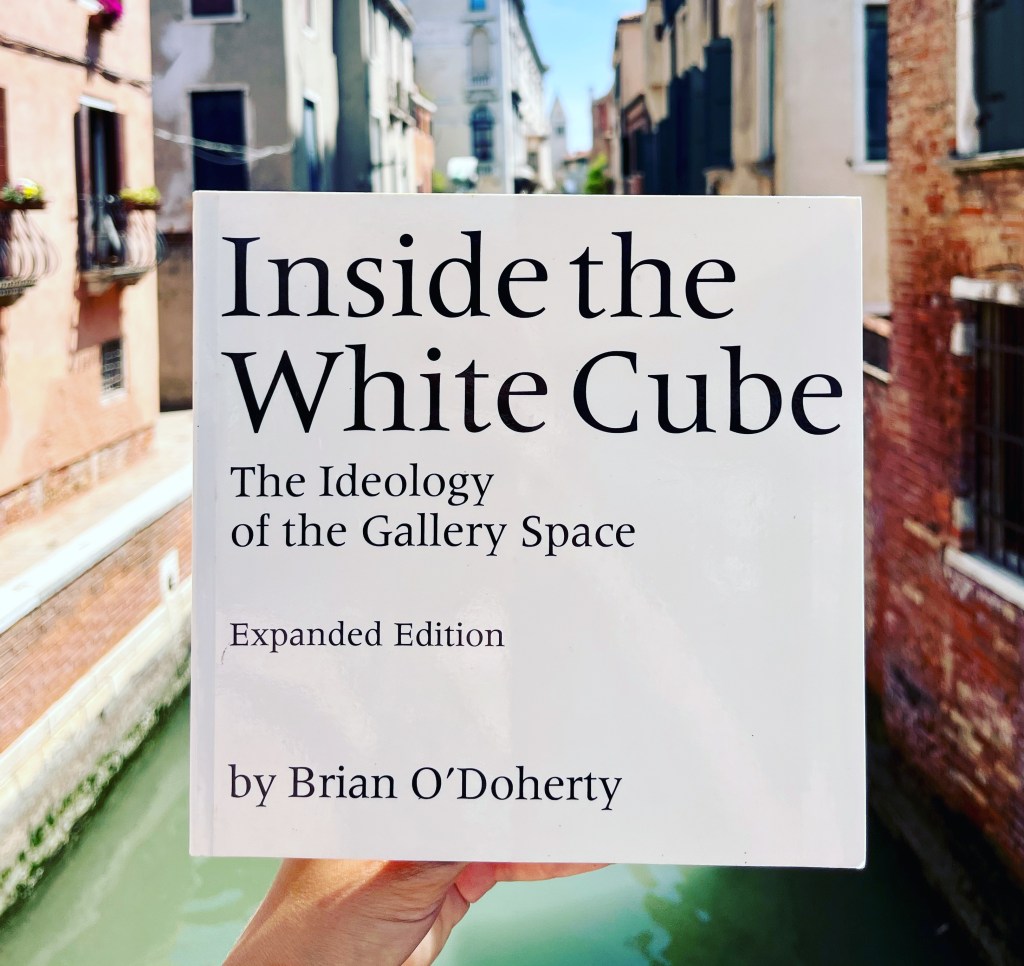

In light of these facts, the abandonment of exhibition practices that reproduced the white cube and the preference for historically connoted places, hybrid environments, and temporary architectures cannot be dismissed as a curatorial trend. Rather, it is an attempt to rethink the aesthetic experience as an embodied experience, as suggested by Vittorio Gallese and David Freedberg, respectively leading figures in research on mirror neurons and in the theorization of embodied simulation applied to art. In these spaces, the context is not a neutral backdrop, but an active variable that dialogues with the work and the viewer. Brian O’Doherty spoke of the white cube as the dwelling place of the Eye, yet the viewer is not just a gaze, but a body sensitive to different types of stimuli, not only visual, traversed by automatic reactions, cognitive biases, and emotional responses that precede any conscious interpretation. Ignoring this dimension means continuing to design exhibitions for a subject that does not exist. In this scenario, curators are called upon to take responsibility: to recognize that every exhibition choice creates a set of conditions that guide perception, attention, and judgment. Being a curator, then, means being a designer of the artistic experience for viewers-interlocutors.

THE MEDIATING ROLE OF THE ART CURATOR

Studies on interaction with space include the analysis of relationships between multiple actors, and research has yielded results that herald changes both in the way art is produced and in the way it is presented to the public: on the one hand, artists are involved, moving from studio or laboratory production to on-site production; on the other hand, users are involved as a fundamental subject in the triangular relationship with the work and the artist. Space is therefore the container in which this relationship takes place. Over time, the role of the curator in the art world has taken on particular importance precisely because of their role as mediators: a bridge between the creative process of artists and the experiential needs of visitors to an exhibition, museum, or any environment where it is possible to enjoy an artistic experience. One exhibition that changed the way we think about art, how it is presented, and the role of those who organize it is Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form, curated by Harald Szeemann in 1969 at the Kunsthalle in Bern, a neutral modernist space that Szeemann used as a testing ground, encouraging artists to produce works directly on site, making the environment part of the exhibition itself. That space influenced the artists and the works produced; if the exhibition had been organized in another environment, the works and the final result would have changed. The idea that art is not only the finished work but the entire process was therefore explored, in which the curator takes on a creative role in relation to the artist.

HOW TO RECONFIGURE THE SPACE OF AN EXHIBITION

Rethinking exhibition spaces today, not only for contemporary art but also for the rearrangement of museum collections, means designing perceptive environments, not simple containers. Taking into account the five senses, not just sight, means, for example, working with light as a variable and non-uniform material, capable of generating areas of attention and pause; with sound, constructing acoustic landscapes that guide the movement of the body in space; with touch, through materials, surfaces, and temperatures that make the space experienceable even beyond vision and also erase that feeling of distance that overwhelms the visitor; on smell, often overlooked but a powerful activator of memory and emotional states; and finally on the temporal rhythm of the visit, which involves the internal sense of the body and duration, helping to combat the so-called “museum fatigue,” when the attention span drops dramatically between the beginning and end of the visit. From this perspective, setting up an exhibition means calibrating, creating conditions in which the work can resonate with a situated body, restoring the aesthetic experience to its sensory and cognitive complexity.

Contexts “speak”, adding a discourse to the work, sometimes completing its meaning, other times being the source of inspiration for its very genesis. Art always happens in relation to a place, a body, a situation. Perhaps it is not a question of abandoning the white cube totally or forever, but of ceasing to believe it is neutral.

Alice Longo

The text has been translated using AI