The proliferation of decolonial rhetoric in the Western art market risks emptying the political meaning of actions aimed at decolonisation. In this scenario, the Palestinian initiative Owneh proposes a different approach: it does not thematise decoloniality, but exercises it through infrastructural practices of solidarity and self-determination.

In recent decades, the language of contemporary art has been enriched by the term “decolonial” to indicate a critical reflection on all institutions, including cultural ones, that have reinforced colonial rhetoric. Exhibitions, reinterpretations of museum collections, open calls, residencies, talks and biennials make decolonisation the main theme of their content, but visitors and readers must be able to distinguish between simple rhetoric and actions aimed at radically changing hierarchies and the system.

FROM LANGUAGE TO STRUCTURE: THE PARADOX OF DECOLONIALITY

First of all, it is useful to make a distinction between postcolonial and decolonial. Postcolonial studies emerged after the end of colonialism and analyse its impact and political, economic, cultural and identity-related legacy on colonised countries. The decolonial approach aims to be not only critical and reflective, but above all active: it aims to create autonomous, self-determining narratives of those peoples historically subjugated by the West.

The great paradox is that many Western art institutions adopt this term in a discursive rather than structural way: while language is updated with terms such as “inclusivity”, “deconstruction” and “care”, important critical issues remain. Above all, there remains a dependence on Western funding – banks, government agencies, multinational corporations – and a vertical curatorial system: the West continues to retain decision-making power over what to represent, perpetuating dynamics of representation of the “other” and thus maintaining control of the narrative.

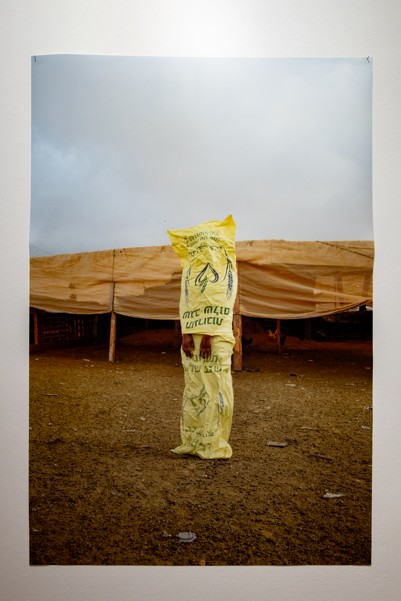

In this way, even works created in radical contexts are absorbed by the system as aesthetics of discomfort, transforming dissent into symbolic and commercial value. Thus, even when a work retains a political message, it is incorporated by institutions that claim to be progressive, converting it into cultural capital and continuing to operate with extractive, colonial logic. Inequality not only remains, but is masked by virtuous language, disguised as inclusion and ultimately aestheticised in the name of “ethical profit”.

Decolonial aesthetics cannot be spectacle: it should be a practice of care. It would be truly decolonial to leave free will – on how and whether to show themselves – to the people who have been victims of colonialism and imperialism. This applies to artists as much as it does to curators. It would be necessary not to thematise decoloniality, but to transform the structure of cultural production.

OWNEH: CURATORSHIP AS INFRASTRUCTURE

The Owneh project embodies precisely this logic. It is an initiative of thirty Palestinian civil society organisations, formed in the wake of 7 October 2023 and the subsequent accelerated genocide perpetrated in Gaza. The principles that led to the establishment of this initiative concern the rejection of global funding systems based on historical exploitation that have prolonged the occupation in Palestine; the rejection of politically conditioned funding that imposes geographical restrictions and operational limitations; and a commitment to strengthening Palestinian resources, volunteerism and solidarity.

The mission is not only economic, it is curatorial in the broadest and most radical sense of the term. By creating a Solidarity Fund, a Resources Basket and an AID Watch platform to monitor donation mechanisms, Owneh practices a reappropriation of the tools of cultural production and distribution. In fact, over 60% of the current signatories to the initiative are artistic and cultural organisations, many of which operate in the visual, performance or community art fields. The primary goal is not to produce or exhibit works, but to curate a context, restoring the political, collective and infrastructural dimension to the curatorial gesture.

To date, the Owneh Initiative, through its Solidarity Prints for Palestine campaign, has raised approximately $20,000 for the Solidarity Fund, created to support Palestinian organisations active in art and culture that refuse conditional donations, and to set up psycho-social workshops that use the arts to help adults and children affected by the trauma of genocide.

In an art system based on power and profit, Owneh stands out as a warning and an alternative, truly decolonial infrastructural and curatorial model. It invites us, as visitors and cultural operators, to think about how much our practices, even artistic ones, are truly free from market logic, conditional funding, and predatory representation.

Decoloniality is not proclaimed, it is practised, in the slow work of redistributing power, resources and possibilities.

Alice Longo

The text has been translated in English using AI